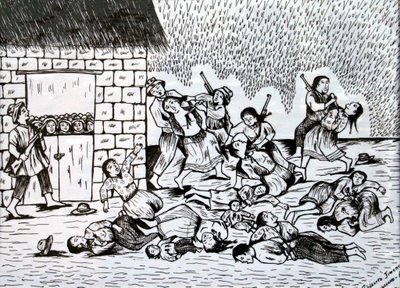

Todas las sangres ends with yet another image of the "yawar mayu", the "blood river," which Arguedas himself here glosses as a "desperate outpouring of tears, the first waters of the rivers in flood, the moment in the dance when the men start to fight" (410).

Todas las sangres ends with yet another image of the "yawar mayu", the "blood river," which Arguedas himself here glosses as a "desperate outpouring of tears, the first waters of the rivers in flood, the moment in the dance when the men start to fight" (410).The yawar mayu is first associated with the "kurku" Getrudis, the dwarf maidservant to the drunken and bedridden Peralta mother. The kurku is also at the origin of Don Bruno Aragón de Peralta's downfall and curse: he had raped her, getting her pregnant with a child who turned out to be a monster, stillborn. It's suggested also that this traumatic act, preying on the most vulnerable, the most subaltern figure imaginable, was also the source of Bruno's mother's misery: "What happened to my mother when the kurku Getrudis gave birth to a condemned thing: a dead foetus covered in bristles?" (25). But by the end of the novel, and with her mistress dead, the kurku finds some kind of redemption for the purity of her voice and the hymns that she composes and sings.

The kurku "has been sanctified" (411) and is "chosen by the Lord" (410) thanks, it appears, to the depth of her suffering. For in Arguedas, suffering, purification, truth, and finally vengeance are always associated. Hence "the river of blood that breaks from her heart [. . .]. At some point, perhaps now, perhaps in a hundred years, her tears will drown the thieves who stole La Esmeralda, the men who had the great silversmith and man of purity, Bellido, killed" (410).

So the yawar mayu is an outpouring of passion long built up in suffering, finally flowing violently and uncontrollably, destroying all that lies in its path. In William Rowe's words, it is "a tidal wave of passion that breaks all boundaries" (Ensayos Arguedianos 92).

And ultimately it is Don Bruno, the kurku's aggressor, who acts out the yawar mayu's cleansing destruction. For following his initial violence as stain, as (self-)condemnation, in the interval Bruno too has learned to suffer. He too becomes, and learns to become, a victim: of his own sexual violence, of his father's curse, and ultimately of the modernizing tendencies introduced by multinational capital that is itself sweeping away all that lies before it.

At the culmination of Todas las sangres, then, two devastating flows meet, conjugate, and compete. The town of San Pedro has been destroyed, its church razed by the mestizos now sidelined from history. Their land has been forcibly appropriated by the Wisther-Bozart corporation, which has suborned the state for the purpose of mineral extraction and capital gain. And Don Bruno, like his mother and father before him increasingly identified with the indigenous multitude, is on the warpath, "a river of blood in [his] eyes; the yawar mayu of which the Indians spoke. The river was about to break its banks over him with more power than any sudden upsurge of the raging torrent that ran through a gorge, five hundred metres beyond his own hacienda's canefields" (437).

Bruno heads first for the neighbouring estate of Don Lucas, a landlord who mistreats and underpays his peons and farm manager alike. Declaring himself an agent of God's own justice, Bruno shoots Lucas dead and hands over his property to the Indians, declaring "I have killed him in order to redeem myself. [. . .] I have killed Don Lucas on orders from on high." "You have suffered more than God himself," he tells the Indians, "you are innocent..." (438). And Arguedas treats this murder and its consequences with remarkable equanimity, suggesting that nature itself covers over the stench almost immediately:

The colonos [indigenous peons] began meeting in council at Don Lucas's hacienda. The former lord's corpse, disfigured and bloody, was by now black with the flies that crawled over it. But the orange trees gave off a gentle light and a bit of freshness to the burning courtyard. (439)Having downed this representative of feudal corruption, Bruno then makes for his brother, Don Fermín, the modernizer whose dream has been to convert the Indians into a wage labouring rural working class. "You sold out to the mining company," Bruno tells him. "You sold out your people; you sold out me" (440). And Bruno shoots, but this time only manages to wound, his brother, with the antique pistol that is his only inheritance from their father.

He then sits down and he "began to weep. His tears fell like a waterfall from his eyes, running over his throat, bathing his face, falling on the old brick floor. [. . .] The mestizo woman couldn't stop herself from crying out 'He's weeping for his child, for his whole life, for his whole life he is weeping!'" (441).

Bruno is stopped, arrested and jailed, and his right-hand man Demetrio Rendón Willka is shot by impromptu firing squad. But the messianism that imbues these final pages of Arguedas's masterpiece continues. Just before he is shot, Rendón Willka, who is by Arguedas's own admission the true if somewhat inscrutable hero of the piece, declares "Our heart is made of fire. Here, and everywhere! We've finally discovered the fatherland. And you, sir, are not going to kill the fatherland." After giving the order to shoot, the captain commanding the firing squad, "as well as the other guards, heard the sound of great torrents shaking the ground far beneath them, as if the mountains had begun to move" (455).

Meanwhile in Lima, the shadowy figure who controls all the strings, the Czar, is conferring with one of his henchmen, Palalo:

"What was that noise, my President?"The question, however, remains as to whether this flooding river is really the cleansing flow of divine judgement, from and after which a new society can be built, a community governed by true solidarity (as William Rowe suggests).

"What noise, Palalo?"

"Didn't you feel it? Listen. It's as though a subterranean river were beginning to rise up."

"It's a bad night, Palalo! You're getting feeble," the Czar replied. "I don't hear a thing. I'm full of health and I'm conscious only of what my will desires."

But the kurku also heard the noise; Don Bruno heard it; and Don Fermín and [his wife] Matilde listened to it with fearful enthusiasm. (456)

Or is it closer to the self-destructive line of flight of an incipient fascism: either the "rivers of blood" shortly to be invoked in the UK by anti-immigration MP Enoch Powell; or perhaps an anticipation of the terror that would come to the Andes a couple of decades later, as Sendero Luminoso brought their own promises of a "river of blood, purifying blood"

No comments:

Post a Comment