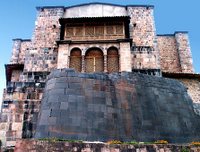

To return to ruins... In the Americas, the Spaniards habitually built on ruins. Recoding or overcoding indigenous space, and with it also the geography of power, they would build churches on the sites of temples that they had (only partially) destroyed, or on top of pyramids, using the existing stones in their construction, the indigenous ruin as foundation. The colonial church lording it over the remains of the native temple served as a history lesson, a constant reminder of indigenous defeat and Spanish dominance.

To return to ruins... In the Americas, the Spaniards habitually built on ruins. Recoding or overcoding indigenous space, and with it also the geography of power, they would build churches on the sites of temples that they had (only partially) destroyed, or on top of pyramids, using the existing stones in their construction, the indigenous ruin as foundation. The colonial church lording it over the remains of the native temple served as a history lesson, a constant reminder of indigenous defeat and Spanish dominance.But in this appropriation the invaders also thereby fixed those ruins: keeping them in place, confirming not only the fact of colonization, but the durability and strength of what had it purported to displace. So the church perched on indigenous ruins enabled a counter-history that could appeal to the ongoing presence of those pre-colonial foundations beneath the precarious veneer of Spanish cultural imposition. This would be a reading emphasizing transculturation and hybridity, and the subterranean persistence of alternative traditions (alternative modernities?) within and beneath imposed cultural forms.

A classic statement of (in this case) the Inca walls' continued vivacity and power is found in José María Arguedas's novel Deep Rivers (Los ríos profundos), which opens with its child narrator's arrival in Cuzco, where he is entranced by the indigenous stonework on which the town's Spanish churches and mansions are built: "The lines of the wall frolicked in the sun; the stones had neither angles nor straight lines; each one was like a beast that moved in the sunlight, making me want to rejoice, to run shouting with joy" (18-19 / 164). The stonework is explicitly compared to a river, "undulating and unpredictable [. . .]. The wall was stationary but all its lines were seething and its surface was as changeable as that of the flooding summer rivers" (6, 7 / 143, 144). Implicitly, the contrast between the vibrant indigenous foundations and the sterile colonial structures (whitewashed and windowless, silent and regimented) built over them, is also compared to the colonial and neocolonial elite's dependency on indigenous labor power.

Even the cathedral, towering incarnation of Spanish force and inculcator of European custom, is built "with the Inca stones and the hands of the Indians" (10 / 149), for as the father observes "what other stones would the Spaniards have used in Cuzco, son?" (11 / 152). The Spaniards imposed form upon these indigenous raw materials, chiseling them to remove their "enchantment." But that neutralization could never be fully successful. The power contained in these remnants of Inca civilization might still one day threaten those who appropriate its strength: the image of the ruins as "flooding summer rivers," as "yawar mayu" or "bloody river" (7 / 144), anticipates the social uprising described at the novel's conclusion, which is described in a chapter entitled, precisely, "Yawar Mayu." No wonder the narrator asks of these structures' inhabitants: "Aren't the people who live in there afraid?" (9 / 147).

For in Arguedas's vision, far from indicating a judgment already pronounced, these vibrant residues of an inextinguishable cultural power foretell a reckoning still to come. As the narrator and his father leave Cuzco, fleeing their humiliation at the hands of a heartless, landowning uncle, they contemplate the remains of Sascayhuamán, the ancient fortress overlooking the town. At first sight these walls seem to blend into their natural surroundings:

In broken ranks the walls settled into the gray, grassy slope. [. . .] My father saw me contemplating the ruins and did not speak to me. Farther up, when Sacsayhuaman appeared, encircling the mountains, and I could distinguish the rounded, blunt profile of the angles of the walls, he said to me, "They are like the Inca Roca's stones. They say they will last until Judgment Day, and that the archangel will blow his trumpet here." (21 / 169)In this reading, what we might term a postmodern celebration of hybridity is conjoined with what we might more tentatively describe as a premodern Andean messianism. Modernity is an interruption, but only temporarily so; the persistence of the Inca ruins, the fact that they are never fully obliterated, indicates the possibility of their future fulfilment, and so (re-)completion.

No comments:

Post a Comment