"I went [to Sarajevo] with many ideas," Juan Goytisolo is quoted as saying in Ben Ehrenreich's "Me and the Major". "I came out only with doubts, no certainties at all." It's not clear, however, whether he is talking of his first visit to the city, in 1993, or his subsequent, 1994, trip.

"I went [to Sarajevo] with many ideas," Juan Goytisolo is quoted as saying in Ben Ehrenreich's "Me and the Major". "I came out only with doubts, no certainties at all." It's not clear, however, whether he is talking of his first visit to the city, in 1993, or his subsequent, 1994, trip. In 1993, if his "Sarajevo Notebook" is any guide, Goytisolo finds that his experience of the city under siege leaves him little time for such doubts:

Life there acquires a vertiginous rhythm and intensity. [. . .] New friendships become deep and long-lived. Sincerity and a longing for truth take hold. One's sense of morality is refined and improved. Discarded concepts hurriedly cast on the dungheap of history are reborn with a new richness and strength: the need for commitment, the urgency of solidarity. Things that previously seemed important wane and lose substances; others slight in appearance suddenly acquire greatness and stand out as self-evident truths. (51)Even so, and despite this insistence on "experiences and images that don't fade from the mind" (51), in practice what emerges from Goytisolo's account of his trip is how heavily mediated he found his encounter with war.

His first dispatch for El País, for instance, opens with a mediation on an advert glanced in Paris as he is en route to the airport. These feature "the blackened manly face of an actor (Tom Berenger?) beneath capital letters of a film title: SNIPER, CRACK MARKSMAN" (3). This "true grit face of the Crack Marksman" is, Goytisolo suggests, "the sublimated ideal and ineffable model of those shooting for real in Sarajevo" (3). But how to distinguish the ideal from the real?

For, however much he lambastes the indifference of the European public, and particularly the reticence of other intellectuals to visit the city ("Attempts by Susan Sontag and myself to bring writers of renown to Sarajevo have ended in fiasco" [47]), the Spanish novelist is continually aware that he himself also remains at one remove from what's going on. His bullet-proof vest, for instance, "compulsory to board UN planes [. . .] privileges me and separates me out from the rest of the besieged" (50).

And at the airport in Rome, headed to Split, though Goytisolo casts an eye askance at his fellow travellers who are, he imagines, on some kind of war tourism thrill, "on their way to the land of Bosnia in their search for a succulent repast, a huge repertoire of genuine horror scenes" (4), is he not reflecting on his own motivations? For is he not, too, but another of these "seekers after such singular encounters" (4)?

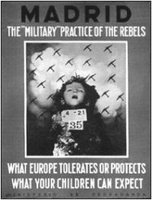

Moreover, this account of violence in the Balkans, and international indifference, is continually framed in terms of Goytisolo's own obsessions with the prelude to fascism in the 1930s, and above all the fate of the Spanish Republic. He has prepared for his experience of Sarajevo by re-reading Antonio Machado's account of Madrid under siege: "Whoever heard the first shells fired over Madrid by the rebel batteries, set up in the Casa de Campo, will always remember one of the most distasteful, distressing emotions . . . that can ever be experienced in life" (49).

Moreover, this account of violence in the Balkans, and international indifference, is continually framed in terms of Goytisolo's own obsessions with the prelude to fascism in the 1930s, and above all the fate of the Spanish Republic. He has prepared for his experience of Sarajevo by re-reading Antonio Machado's account of Madrid under siege: "Whoever heard the first shells fired over Madrid by the rebel batteries, set up in the Casa de Campo, will always remember one of the most distasteful, distressing emotions . . . that can ever be experienced in life" (49). Goytisolo (born, Barcelona, 1931) surely never heard those shells over Madrid. Is he now, "profoundly reliving the feelings of the poet canonized by our socialist politicians" (49), finding in Sarajevo an aide mémoire to reconstruct an intangible scene of Spanish trauma?

But is this not too easy a critique? Despite his claims to experience and the authenticity of his encounter with the Balkan conflict, Goytisolo hardly hides or shies away from the multiple mediations that frame his account. His point, indeed, is not that there has been silence about the fate of Sarajevo, or even that much obfuscation: he asks rhetorically whether the tourists, who he has later decided are in fact off to a beach holiday on the Dalmatian coast, can "be unaware of what is happening only a hundred kilometers away?" (6). Of course not. "We cannot plead ignorance: the journalists and photographers dispatched to Sarajevo and the war fronts have generally 'covered' the news with exemplary honesty and courage" (47). It is not that we do not know. It is that we do not do anything about our knowledge.

The difference between Sarajevo in the 1990s and Madrid in the 1930s, then, is properly posthegemonic. The issue is not ideology or truth, but affect and habit. For some reason, Europe in the 1990s is no longer affected by what happens at or within its borders. The problem is not doubt--if only it were--or the unreliability of the media. It is a question of habituation.

Finally, then, if we lack solidarity, it is not because we lack imagination. What's required, rather, is an affective rapport, a resonance that is felt physically. We need to be moved, immediately if without resort to ideologies of authenticity.

No comments:

Post a Comment