Some days ago,

Organic Warfare drew my attention to an entry on the so-called

"Salvador Option". Unfortunately, his blog has all comments disabled, but you can see some of our subsequent discussion

here.

More recently, I read a long article by Mark Fuller entitled

"For Iraq, 'The Salvador Option' Becomes Reality", which draws on a whole number of sources, not least a January

Newsweek article on "The Salvador Option" that summarizes this "option" as follows:

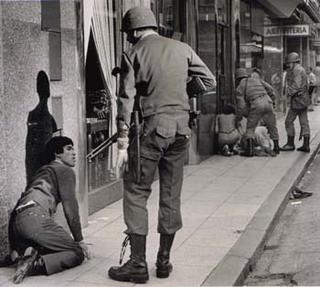

The Pentagon is intensively debating an option that dates back to a still-secret strategy in the Reagan administration’s battle against the leftist guerrilla insurgency in El Salvador in the early 1980s. Then, faced with a losing war against Salvadoran rebels, the U.S. government funded or supported "nationalist" forces that allegedly included so-called death squads directed to hunt down and kill rebel leaders and sympathizers. Eventually the insurgency was quelled, and many U.S. conservatives consider the policy to have been a success—despite the deaths of innocent civilians and the subsequent Iran-Contra arms-for-hostages scandal. [. . .]

Following that model, one Pentagon proposal would send Special Forces teams to advise, support and possibly train Iraqi squads, most likely hand-picked Kurdish Peshmerga fighters and Shiite militiamen, to target Sunni insurgents and their sympathizers, even across the border into Syria

See also the follow-up article,

"Death Squad Diplomacy", by Christopher Dickey, who was a long-time correspondent in Salvador during the 1980s.

Now, I think that it is worth comparing Salvador and Iraq, though not necessarily in the ways that the above articles suggest. Indeed, I agree with Fuller that there are many ways in which Colombia is probably a better direct comparison. Panama might be another, as one of the US's first experiments in "regime change" in the modern style, and so successfully so (from the US perspective) that it might have given false confidence to those who plotted the Iraq War. Panama's president Noriega had, after all, like Hussein been a strategic ally in a strategically important location--in Noriega's case because he was sitting on the canal. But the US turned against their former strong man in the region, bringing him down in a full scale invasion (ordered by Bush père) on the flimsiest of excuses, with the minimum of US casualties. More details can be found from

The Panama Deception, a film that was the

Fahrenheit 911 of its day, a controversial 1992 Oscar winner. See also John Weeks and Phil Gunson's

Panama: Made in the USA.

At the same time, there are many differences between Iraq and Salvador, Colombia, or Panama. None of the three turned into

"failed states" in quite the spectacularly implosive and dangerous manner that Iraq has done so. None of these Latin American conflicts had ethnic or religious components. None were about exploitable resources. (Though Colombia does of course have an export crop that has found a fertile market in the USA, there are as yet no multinationals poised to take over its production and distribution.) None was ever more than briefly the focus of world attention. Still here are some snippets of thoughts about Salvador...

What is it about tall buildings? They seem to provoke a kind of fatal attraction among those that, following Deleuze and Félix Guattari, we could call nomads--those homeless, mobile, components of the war machine for whom "weapons are affects and affects weapons" (

A Thousand Plateaus 400). New York's twin towers had, after all, been attacked before, while the height of success for El Salvador's Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) and perhaps the single most important moment of that country's ten-year civil war, was the guerrilla group's capture of the San Salvador Sheraton, one of the city's tallest buildings, in November 1989. As José Ignacio López Vigil puts it: "We attacked the big hotel because it was the highest point in the neighbourhood" (

Rebel Radio 229).

Beyond strategic concerns, perhaps it is also that building upwards has been a defining mark of homogenizing unification from Babel to Taipei 101. Babel still epitomizes the dream of unimpeded and transparent communication, but it was also merely the first such project (and the first such tower) to fall. One may hesitate to call Babel "modern," but like the Pyramids (the world's highest manmade structures in the ancient era) its height required a kind of cooperation that ultimately only modernity would enable. It's no coincidence that Kuala Lumpur's city center, with the Petronas towers site of among the world's tallest buildings today, is an "intelligent precinct" set at one end of the world's most ambitious communications project, Malaysia's "Multimedia Super Corridor" (MSC), an area of land the size of Singapore that will be fully "wired" and will be site of two new "smart cities." Tall buildings epitomize the desire for transcendence, whether religious, state, or corporate; they enable surveillance and the dream of transparency; it is from the symbolic and material vantage point that height provides that social life can be stratified and ordered.

In El Salvador, the Sheraton proved to be the locus of far more than simply symbolic power. Attracted to its height, and so to its commanding position within the fashionable neighborhood of Escalón in which they were launching a counter-attack during the November 1989 offensive, the FMLN "had no idea who was inside: none other than the secretary general of the Organisation of American States, João Baena Soares, who was in El Salvador to learn about the war and ended up seeing it up close" (López Vigil,

Rebel Radio 229). Still more significantly, also staying at the hotel, on the top floor, were twelve US green berets, who suddenly became in effect prisoners of the FMLN. The US president at the time (another George Bush) sent down an elite Delta Force special operations team from Fort Bragg, ready to intervene directly in the Salvadoran civil war for the first time. But after twenty-eight hours the guerrillas left the hotel of their own volition; as far as the press were concerned, they simply vanished: "Reporters who approached the hotel just after dawn [...] said there was no sign of the rebels who took over part of the hotel in the exclusive Escalon district of the capital" (Simon Tisdall, "Green Berets walk free from Salvador Siege,"

The Guardian [23 November 1989]: 10). Another report again emphasizes the sudden disappearance of the guerrillas ("the rebels were nowhere to be seen") and contrasts it with the US soldiers' territorial immobility and reliance upon direction from above: "The Green Berets, however, were still behind their barricades. 'We've had no orders so we're staying here,' one of them said to a large crowd of journalists" (Tom Gibb, "Sheraton siege ends as rebels withdraw,"

The Times [23 November 1989]: 10).

Across the country the offensive was now over. The FMLN had shown that they could mount and sustain an engagement at the very heart of middle class Salvadoran society--while, elsewhere, the government had shown that it had no qualms about bombing working class suburbs from the air, or about murdering some of the country's leading intellectuals, six Jesuit priests who worked and lived in the Universidad Centroamericana. State terror more than matched any "outrageous act of terrorism" (in the words of a US State Department spokesman [quoted in Tom Gibb, "US alert as rebels hold four in hotel,"

The Times (22 November 1989): 1]) that may have been committed by the insurgents. A realization on both sides of the resulting impasse led to the peace accords that ended the war.

Simultaneously, across the world the Cold War was now ending. The FMLN offensive (November 11th to 23rd) had taken place in the brief interlude between the fall of the Berlin wall (on November 9th) and the fall of the first East European communist regime--the Czech president quit and Dubcek returned to Prague on November 24th. The November offensive ("in all probability, the biggest guerrilla offensive ever mounted against a Latin American government" [McClintock,

Revolutionary Movements in Latin America 84]), and particularly the incident in the Sheraton with which it ended, was then a hinge: both the last confrontation of the Cold War era and the first post-Cold War conflict, a premonition of future actions against tall buildings. In the incident at the Sheraton, the FMLN crossed the boundary that separates subaltern from hegemonic project, without for that entering into the space of hegemony itself. Rather, they provided a foretaste and example of posthegemony.

And The Alamo's Santa Anna, played with some panache by Emilio Echeverría, is indeed the very model of a modern tyrant: cowardly and effete, more concerned with pomp and appearance than tactics or efficiency, he callously sacrifices his soldiers and ignores his officers' pleas to respect the rules of war.

And The Alamo's Santa Anna, played with some panache by Emilio Echeverría, is indeed the very model of a modern tyrant: cowardly and effete, more concerned with pomp and appearance than tactics or efficiency, he callously sacrifices his soldiers and ignores his officers' pleas to respect the rules of war.