Monday Arguediana

In some ways, and perhaps rather strangely, José María Arguedas's last book,

El zorro de arriba y el zorro de abajo, bears more than a passing resemblance to the

metafiction characteristic of late twentieth-century postmodernism.

The book is, after all, studded with authorial interventions, written as diary entries, that interrupt the narrative and reflect on the process of writing itself, as well as on the plot and the characters it contains. (Many of these, including the first and final diaries, plus the epilogue and the speech "No soy un aculturado," can be found

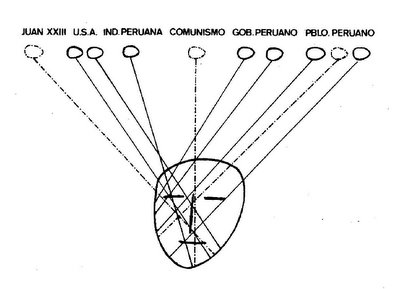

here.) At an intermediate level, the novel also incorporates another pair of commentators in the eponymous foxes (elements drawn from indigenous folklore) who meet and watch over the action as it unfolds in the Peruvian port city of Chimbote.

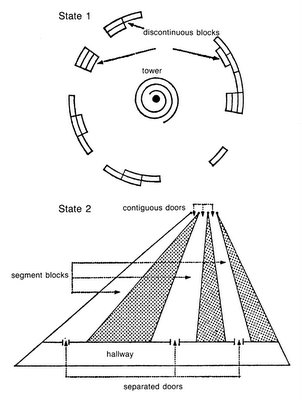

Los zorros is, moreover, an eminently nonlinear and open work: it is composed of a series of brief stories, often presented as long dialogues as individual characters recall their past histories and so situate themselves within the rapid transformations of capitalist development affecting them all.

These individual narrative arcs are never fully brought together. Rather they coexist somewhat uneasily, precariously shoulder to shoulder in the shared space of a city that has sprung up almost from nowhere around the fish processing factories driving this dislocated pole of economic expansion.

Plus there is the fact that the book remains unfinished. In the "final diary entry" Arguedas outlines how he might have continued, and reveals some of the fate that he has had in store for individual characters. Then among the other paratexts with which it concludes is a letter from the author to his publisher, apologizing for the text's incomplete state, describing it as "a body that's half-blind and deformed but perhaps still able to walk on its own" (201).

But this same letter reveals what distinguishes the novel from the flamboyant literary exhibitionism of a John Barth or an Italo Calvino. In a postscript, Arguedas writes: "P. S. (on my return to Lima) In Chile I got hold of a .22 caliber revolver. I've tested it. It works. It will do. It won't be easy to choose the day, to carry it out" (203). This is not, in other words, some playful metafiction in which textuality is all. This is a book that begins with a discussion of suicide, ends with a suicide note, and is signed with the author's own dead body.

For Alberto Moreiras observes that in a further letter, also included as part of the novel, dated November 27, 1969, the day before his suicide

Arguedas notes almost casually that his novel is "casi inconclusa" ["almost unfinished"]. It is "almost unfinished" because he had not yet killed himself, but he had already made the irrevocable decision to do so. After Arguedas's suicide the novel will and will not be finished, simultaneously and undecidably [. . .] Arguedas's suicide is, properly speaking, the end of the book. (The Exhaustion of Difference 204)

But the suicide is only the last of a series of breakdowns that run through the text, and that have to be read as at one and the same time corporeal, material, as well as textual. And just as the (here very literal)

death of the author both puts an end to

what Barthes calls the "work" and gives birth to the "text," so these breakdowns both bring writing to a halt and at the same time, by doing so, show the process of its operation, enabling it to start up again.

What we have here, in other words, is a revelation of the machinic qualities of Arguedas's writing, and perhaps writing

tout court. And in some way it may have been this revelation that proved too much for Arguedas himself.

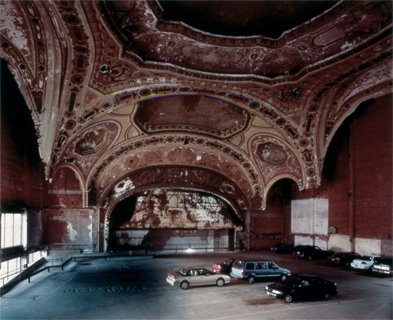

Yet this notion of a productive factory, driven by desire, and the becoming-machinic of those attending to it, is an explicit theme within the novel itself. For in an extended sequence, perhaps the novel's longest, at the (dead?) centre of the book, we are shown around a Chimbote fish factory, shown the workings of the mechanisms that have enabled the city's prodigious growth as in a few short years it has concentrated all the forces of international capital: "corralling in Chimbote bay the Hudson and the Marañon, the Thames and the Apurimac" (76).

The factory manager takes his guest (and so also the novel's readers) to the heart of the productive process, the centrifuges in which the fish oil is extracted, which "nobody has observed." At the threshold, the guest, Diego, takes a step back in some trepidation. And indeed the manager warns of possible danger: "The cyclones have never burned anyone, but even so..." And then there, at the heart of this near-deserted factory in which the workers merely oversee the machines, the membrane between human and machine is suddenly permeable:

The visitor stopped short a few steps in. His breathing no longer in the control of his own lungs, but governed by the eight machines; the environs was all lit up. Don Diego started to turn around with his arms outstretched; some kind of bluish vapour began escaping from his nose; the sheen of his leather shoes reflected all the light and compression there inside. A musical happiness arose, something like that produced by the tallest breakers that sound on unprotected beaches, threatening nobody, developing on their own, falling on the sand in torrents more powerful and more joyful than the waterfalls in Andean rivers and streams; so a happiness churned around the vistor's body, churned in silence and Don Angel and the group of workers sat there, eating their anchovy soup, leaning on the gallery walls, felt that the force of the world, centered in the dance and in these eight machines, lapped at them, and made them transparent. (103-104)

This is an extraordinary epiphany, again at the heart of the book and in the entrails of industrial capitalism: a vision that seems to supersede even the "yawar mayu," the Andean rivers in flood. A new messianism opens up in a posthuman conjuncture of nature, man, and machine.

Is there a key here to an Arguedas-machine, comparable to the "Kafka-machine" mapped by Deleuze and Guattari who argue that "a writer isn't a writer-man; he is a machine-man, and an experimental man" (

Kafka 7). For surely Arguedas and Kafka have much in common: writers of minor literatures in a tongue that is not their own, stuttering, undoing, and causing breakdowns in the major literature and the culture of majorities.

The machines in the Chimbote factory "shit gold; that is life, isn't it?" (100). Arguedas likewise, and like the character Esteban who is dedicated to spitting out and selling the coal dust in his lungs, aims to make of his mutilated body and psyche a machinic apparatus for the selection and intensification of affects, for the alchemical transformation of shit and suffering into gold and happiness.

Of course, the machine only works in and through its breakdowns: as Deleuze and Guattari say elsewhere, the desiring-machines "work only when they break down, and by continually breaking down" (

Anti-Oedipus 8). That's their danger and the risk that the writer takes. And at some point, for Arguedas, that breakdown was terminal. But not before he'd revealed the epiphany at the heart of his anguished, delirious writing assemblage.