And behold, thanks to Abebooks, I now have a copy (autographed, no less) of the Diagram Poems. They really are extraordinary.

The poems were inspired by accounts of the Uruguayan Tupamaro guerrillas in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The Tupamaros were a pretty fun-loving, performative lot, at least at the outset. As Lawrence Weschler notes, they projected the image of a "marriage of Chaplin and Che. [. . .] Student radicals all over the world looked upon their Uruguayan counterparts with undisguised admiration. Nowhere else did young radicals seem to bring to their activism quite the brio, quite the panache, that the Tupamaros of Montevideo managed" (100-101). They engaged in a form of guerrilla theatre, showing a measure of humour and consideration for the inadvertent consequences of their action. For instance, as A J Lagguth records:

On one occasion, they burst into a gambling casino and scooped up the profits. The next day, when the croupiers complained that the haul had included their tips, the Tupamaros mailed back a percentage of the money. (qtd. 103)They attacked symbolic targets. They performed a kind of armed situationism.

Once, in the wee hours of another morning, they ransacked an exclusive high-class nightclub, scrawling the walls with perhaps their most memorable slogan: O Bailan Todos o No Bailan Nadie--Either everybody dances or nobody dances. (104)Gradually, however, the game became bloodier and more deadly serious, on both sides. And June 1973 saw what Weschler calls "the final culmination of a five-year-long slow-motion coup" (110) with the installation of full-blown military authoritarianism.

Oliver's poems--and the all-important diagrams--are neither celebration nor condemnation of the Tupamaros. They are, perhaps, an attempt precisely to diagram the forcefields within which they operated, and into which they intervened. Oliver doesn't shy away from comedy, especially in the opening sequences: note the cartoon-like qualities of the early diagrams. Nor from tragedy: the final annotation on the final diagram refers simply to the "Festival of the wild beasts" while the accompanying poem includes the lines

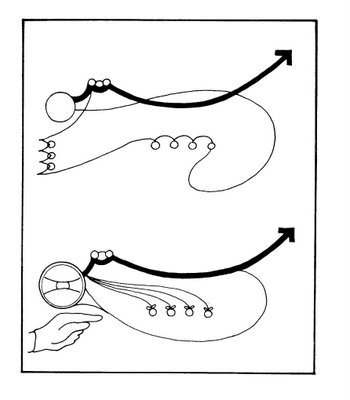

it all turns so really funereal for usHere, meanwhile, are the opening couple of diagrams in the book. The first, Oliver describes as "of a general co-ordinator's movements as he visits the various operations by car."

as brave as that and as flawed

just a final diagram almost straight

and a heart on which the diagram is scored

beside the deaths of innocences we have known

and even caused a little in the scarface heart.

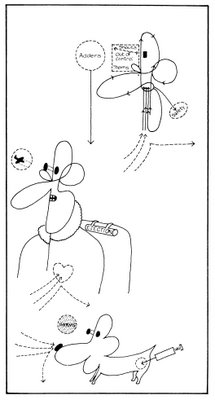

The second outlines a more complex scenario, in which

one group of raiders, some disguised as airmen, arrives in three separate parties to take over a police station. (Beforehand, they have reconnoitred the station during several visits, posing as members of the public. They brought the same dog, twice, for vaccination formalities.) They begin the seizure by rounding up policemen and placing them, eventually, in cells. A police sergeant, overlooked, appears from a dormitory, fires warning shots to the outside streets, darts through corridors, and aims at the invaders from a central patio. He takes refuge, wounded, in the dormitory and finally gives himself up. Two other police officers walk into the building and are overpowered but a third escapes. These prove crucial hitches in the overall plan.

And here's a snippet of the accompanying poem, "P. C.":

Like an adder, the sergeantMore on this anon. In the meantime, if anyone has any idea of the essay I half-remember reading on these poems, from at least fifteen years ago, I'd be most grateful for a reference.

swerves to cold. From a doorsill he snakes

into the internal.

The hope of speed is stung in a home of pyjamas

or a bullet to the fancy for a long, long time.

At last, in a dreamy sweat, movement

goes peaceably to the sagpit, safety.

No comments:

Post a Comment