The question regarding democracy is whether or not we can imagine an anti-democratic, or better non-democratic, politics. In other words, is politics tied to democracy, or can it be imagined beyond democracy?

(A supplmentary question might then be whether or not we can and should imagine a beyond to politics itself: a post-politics.)

The prevailing consensus would seem to be that politics is unimaginable without democracy, that it is only democracy that opens up the possibility for politics. Without democracy, all we are left with is (variously, or perhaps in combination) power, administration, fanaticism, hatred.

Such is the view of Ernesto Laclau, but also, for instance, Jacques Rancière, who writes:

There is politics, the art and science of politics, because there is democracy. Politics is encountered as already present in the factuality of democracy, in the very strangeness of the combination of words which joins the unassignable quantity of the demos to the indefinable action of kratein. (On the Shores of Politics 94)

Rancière traces the mixed fortunes of both politics and democracy from its invention in Athens to the current "end of politics."

For Rancière, democracy (and so politics) is characterized by three conditions, which together constitute a split and antagonistic subject:

Politics is a function of the fact of democracy, of the way in which democracy's factuality presents itself in three forms: the appearance deployed by the name of the people, the imparity of the people when counted and the grievance connected with the antagonism between rich and poor. (96)

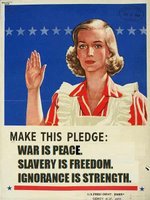

In our post-political, post-democratic age, all three of these conditions are now undermined, ironically for the sake of democracy's correction or perfection, in other words to erase the split that (for Rancière) characterizes the democratic subject:

Exhibition in place of appearance, exhaustive counting in place of imparity, consensus in place of grievance--such are the commanding features of the current correction of democracy, a correction which thinks of itself as the end of politics but which might better be called post-democracy. (98)

There is, however, a tension in this formulation: first, the declaration that this correction only "

thinks of itself as the end of politics" implies that in fact politics continues; and second, the admission that this correction of democracy is itself in the name of democracy implies that it is less post-democratic than, in fact, a limit

internal to democracy.

Meanwhile, the threat of post-democracy, as Rancière sees it, is that it summons up "the spectre of the great all-devouring Whole" (65), "the rule of the principle of unification of the multitude under the common law of the One" (88), an "ochlocracy" (33), that is, the "turbulent unification of individual turbulences" (31). And what is most monstrous about this threat, we are told, is that its unity is impossible, fantasmatic, and depends only on the violent, passionate exclusion of the racialized other; it conjures up therefore a world of "fear and hate" (36), "the return of the animalistic aspect of politics" rather than "the democratic virtue of trust" that inheres in democracy's "polemical space of shared meaning" (60).

So democracy has to be split, has to depend on inequality and grievance, so as to ward off the threat of radical difference incarnated in the multitude and its purported others.

We have here, therefore, something like a mirror image of Negri's conception of the multitude--with, of course, the difference that for Negri the multitude's passion is not hatred but

love.

Moreover, Hardt and Negri's wager is that the (self-)rule of the multitude might still be termed democracy; indeed, that in that it escapes the entire problematic of (in)equality and identity that (as Rancière points out) bedevils democratic theory and practice, replacing it with the combination of commonality and singularity, multitudinous immanence is now a better bearer of the name democracy than are actually existing political regimes. "Post-democracy" therefore invokes this new, more democratic, democracy of pure immanence.

Angela Mitropoulos and Brett Neilson condemn this move as at best a form of "diplomacy" (and "diplomacy is already a technique of statecraft"), but more importantly because it thereby "fails to confront the politics of the

demos and the

kratos that invocations of democracy set to work" (

"Cutting Democracy's Knot"). I'm not so sure; refusing to confront democracy's entanglements might also be seen as a strategic evasion, another mode of cutting the knot.

More importantly, however, it would be worth taking seriously the notion that the multitude might equally be characterized by hatred as by love; I see no obvious reason for simply assuming that the multitude's passion is the latter rather than the former. Certainly not if we look at groups that are otherwise organized very much along the lines that Negri argues are characteristic of the multitude:

Sendero Luminoso or al Qaida, for instance. We need, at the least, to distinguish between multitudes good and bad--though that distinction may turn on ethics, rather than on politics.

Or take the image that provides Rancière with his book's title, of maritime flows and desires that have to be domesticated by shepherds on shore. Rancière writes that

The great beast of the populace, the democratic assembly of the imperialist city, can be represented as a trireme of drunken sailors. In order to save politics it must be pulled aground among the shepherds. (1)

But without romanticizing shipboard life and lusts, and while recognizing that it was maritime power that built terrestial empires, can we not

rescue a politics of perhaps something like democracy from the interstitial, unbounded spaces of the high seas?

Crossposted to Long Sunday.

Castro dies. Nothing happens. So some fool Florida gusano tries to assassinate Raúl, but fails. We find out that US special services have helped him out on the sly, and that Cheney's given them the nod. Scandal. Cheney has a heart attack. Bush is impeached. Hillary is the only one with the machine to step in, and so in these exceptional circumstances she becomes president. But the perverse result is that, as the first woman commander-in-chief doesn't want to look soft on defence... she invades Cuba by the end of the year.

Castro dies. Nothing happens. So some fool Florida gusano tries to assassinate Raúl, but fails. We find out that US special services have helped him out on the sly, and that Cheney's given them the nod. Scandal. Cheney has a heart attack. Bush is impeached. Hillary is the only one with the machine to step in, and so in these exceptional circumstances she becomes president. But the perverse result is that, as the first woman commander-in-chief doesn't want to look soft on defence... she invades Cuba by the end of the year.