It was Marx's 188th birthday yesterday, as

s0metim3s,

carlos rojas, and

Steven Shaviro, among others, note. I hope to write up something

apropos before long.

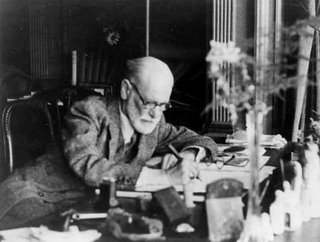

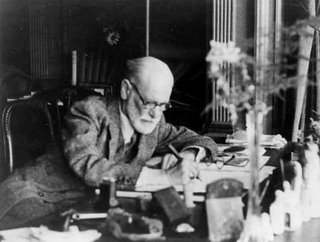

But it is Freud's today. And old Sigismund would be 150 were he still alive, which is quite a milestone by anybody's standards.

Moreover, I have returned to thinking about

ruins, one of Freud's many obsessions. Freud took a keen interest in archaeology, and his home in Hampstead was filled with a collection of over 2,000 curios that had been excavated from the Ancient World: no wonder the London Freud Museum should comment that, surrounded by his antiquities, Freud

"worked in a museum of his own creation". (See also

The Vienna Freud Museum.)

As the museum

further indicates, these curios were prized for more than their aesthetic value alone. Freud believed they told something of the truth of pyschoanalysis and its theories of the unconscious:

One example of this is Freud's explanation to a patient that conscious material "wears away" while what is unconscious is relatively unchanging: "I illustrated my remarks by pointing to the antique objects about my room. They were, in fact, I said, only objects found in a tomb, and their burial had been their preservation."

Freud often compared the unconscious to buried ruins, and the task of the analyst to that of the archaeologist, uncovering ever deeper strata for the prizes hidden in the depths, clues to the ways of life only dimly discerned from mere surface inspection.

But in a late essay, Freud turns this metaphor on its head. In "A Disturbance of Memory on the Acropolis," ruins stand for what is clearly in view, in front of the analyst's face. And the issue here is why what is so straightforwardly visible, uncompromisingly material, should be strangely denied or disavowed.

Written in 1936, "A Disturbance of Memory" is in fact a kind of birthday present, dedicated to the Nobel Prize-winning writer

Romain Rolland "on the occasion of his seventieth birthday." And age, old age, is a constant theme. Freud notes that he himself is "ten years older" than Rolland, and that his "powers of production are at an end" (

On Metapsychology 447). There is, therefore, from the outset a melancholy note sounded, a lament for times past and fading strength.

The essay's topic is a recollection from 1904 ("a generation ago" [447]) that has "kept on recurring to [his] mind." It concerns a trip Freud took with his brother, a holiday south to the Mediterranean, first to Trieste, with the intention of continuing on to Corfu. In Trieste, however, the brothers' plans changed. A business acquaintance advises against Corfu and strongly suggests that the two sail for Athens, instead. For some reason, this suggestion provokes in the two travellers "a discontented and irresolute state of mind" (448). Yet, almost unconsciously ("as though it were a matter of course") they book a passage for Athens, and soon enough set out to see the sights.

Freud's reaction to the ancient ruins of which he has heard so much is, he admits, decidedly curious:

When, finally, on the afternoon after our arrival, I stood on the Acropolis and cast my eyes around the landscape, a surprising thought suddenly entered my mind: "So all this really does exist, just as we learnt at school!" To describe the situation more accurately, the person who gave expression to the remark was divided, far more sharply than was usually noticeable, from another person who took cognizance of the remark; and both were astonished, though not by the same thing. The first behaved as though he were obliged, under the impact of an unequivocal observation, to believe in something the reality of which had hitherto seemed doubtful. [. . .] The second person, on the other hand, was justifiably astonished, because he had been unaware that the real existence of Athens, the Acropolis, and the landscape around it had ever been objects of doubt. What he had been expecting was rather some expression of delight or admiration. (449)

The ruins are an instance of what is incontrovertible, plainly in front of Freud's face, but whose reality for some reason some part of him chooses to doubt. What should be a source of affirmation ("delight or admiration") becomes instead the occasion for a deep scission within the self. And Freud goes on to describe this as "a 'feeling of derealization' [

'Entfremdungsgefühl']" (453).

This derealization is itself, of course, another mode of denial, of repression. And Freud notes that it is the mirror image of the fantasy, or the "hallucinations," more readily associated with psychic disturbance, and indeed with Freudian theory. Where a fantasy conjures up the unreal, the delusion, its counterpart derealization conjures away what is plainly real. And if fantasies are always images of possession, of incorporation, "in the derealizations we are anxious to keep something out of us" (453); "they aim at keeping something away from the ego, at disavowing it" (454).

Interestingly, Freud takes as a prime example of derealization the famous "moor's last sigh," when the last ruler of Muslim Andalucía, Boabdil, reacted to news of the fall of Alhama:

He feels that this loss means the end of his rule. But he will not "let it be true," he determines to treat the news as non arrivé. The verse runs:

"Cartas le fueron venidas

que Alhama era ganada:

las cartas echó en el fuego,

y al mensajero matara"

["Letters had reached him telling that Alhama was taken. He threw the letter in the fire and killed the messenger."] (454-455)

But Freud observes that what is "truly paradoxical" about his own behaviour on the Acropolis is that, far from denying or repressing a trauma or displeasure, his defence mechanism serves to ward off "something which, on the contrary, promises to bring a high degree of pleasure." At last, a dream attained: why deny it, as though it were "too good to be true" (450)?

And Freud's explanation takes recourse in the concept of the super ego. Rather than warding off an external threat, derealization is symptom of an internal frustration, which "commands [the sufferer] to cling to the external one"; and the internal frustration itself is "a residue of the punitive agency of our childhood" (451).

So back further in time Freud goes: beyond the scene of writing as an eighty year old in 1936; beyond his recollections of a trip undertaken at the age of forty-eight, in 1904; back to his childhood, to his schooldays in the 1860s, and back (but of course) to the familial scene, to the figure he refers to, refracted through an anecdote in which he compares himself to Napoleon, in the strangely distanced, formal and foreign, turn of phrase "

Monsieur nôtre Père" (456).

It is not, then--and this at last is the "disturbance of memory" signalled in the essay's title--that at school the young Freud had doubted the Acropolis's existence. Rather:

It seemed to me beyond the realms of possibility that I should travel so far--that I should "go such a long way." This was linked up with the limitations and poverty of our conditions of life in my youth.

[. . .]

But here we come upon the solution of the little problem of why it was that already at Trieste we interfered with our enjoyment of the voyage to Athens. It must be that a sense of guilt was attached to the satisfaction in having gone such a long way; there was something about it that was wrong, that from earliest times had been forbidden. It was something to do with a child's criticism of his father, with the undervaluation which took the place of the overvaluation of earlier childhood. It seems as though the essence of success was to have got further than one's father, and as though to excel one's father was still something forbidden. (455, 456)

No surprises here, then. In a caricature of pop cult images of pyschoanalysis, the whole incident with the ruins comes to revolve around an Oedipal anxiety: the desire to supersede the father, and the attendant feelings of guilt. The short-cut to interpretation, as always, being to intone in heavily accented English: "Tell me about your father."

Fortunately, and this is the great delight with Freud, he leaves himself open to another interpretation altogether: one that is right in front of his face, if only he'd see it.

For again, the essay ends as it had started, with a lament as to the analyst's own declining powers, a nostalgic sigh from one old man to another, on the occasion of the somewhat younger man's birthday:

And now you will no longer wonder that the recollection of this incident on the Acropolis should have troubled me so often since I myself have grown old and stand in need of forbearance and can travel no longer. (456)

Freud admits that he himself is now needy and dependent. He lacks the mobility of his youth. He can easily be overtaken. Is not the issue then less his own father, than his position as father, literal and metaphorical, of the movement that he started but can no longer keep up with?

Literal in that ("Tell me about your daughter"?) Freud has already referred to his daughter, Anna, precisely at the moment that he introduced the theme of ego defences:

An investigation is at this moment being carried on close at hand which is devoted to the study of these methods of defence: my daughter, the child analyst, is writing a book upon them. (454)

Surely there are some revealing turns of phrase here, though one would have also to examine the original German text.

The "child analyst," in English at least, might suggest both that she analyzes children, and that she is herself still (to Freud) but a child, if only in terms of analysis. But is there not some anxiety in the assurance that Anna remains "close at hand": close because he now needs her close by, to continue his legacy; too close to comfort because it is she who is the future author, catching up on Freud while his own "powers of production are at an end"; perhaps too likely to stray, close now but soon distant, superseding or betraying her father?

And metaphorical in that... Well, can we not read this whole tale, and the birthday essay that has accreted around it, as a metaphor for the fate of psychoanalysis itself? Is not the split subject that gazes at the old, split rocks of the Parthenon the split subject of pyschoanalysis?

Though Freud starts to discuss "the extraordinary condition of '

double conscience'" as a means to understand this condition (453), all too soon he disavows this very concept: "But all of this is so obscure and has been so little mastered scientifically that I must refrain from talking about it any more to you" (454). Freud the little Napoleon chooses silence, repression, because of an anxiety patently about the possibility of losing mastery, about the limits of a method he would like to convince us is in some way scientific.

And yet it is precisely this double consciousness that is most startling, most plainly in view in the entire anecdote! Indeed, the entire story would be impossible were it not for the "second person," whose astonishment at the "first person"'s derealization functions to insist that his denial is indeed in some way pathological. This second person is on the side of reality, of affirmation, of a literal reading of what stares the analyst straight in the face.

And is not this second person, found within the analyst, and enabling his melancholy remembrance, his sad intepretations, the hint of a psychoanalysis that would not be bound to the super ego, to the childhood traumas imposed by a fading father figure? Doesn't this second person, the other side of Freud's double consciousness, hold the keys to a schizoanalysis? A schizoanalysis that begins with the "split personality" (453-454) that so shakes Freud and his illusion of scientific mastery that he has to guard his silence and return (oh, once again) to the old mournful tale of fathers and sons, itself only a cover for a still more pathetic anxiety over fathers and daughters?

It is double consciousness, which includes the wild, unscientific analysis so feared by Freud, that makes the entire procedure productive, that gives the lie to Freud's own self-pitying complaint that production is "at an end." If only it were at an end, thinks Freud; if only he could put a stop to it. It's so evidently in his face. And yet it is this other side to pyschoanalysis that he is most anxious to disavow.

Despite himself, Freud let a genii out of the bottle that still, 150 years after his birth, returns to enliven but also (affirmatively, joyfully, impiously, youthfully playing among the ruins) traduce and betray, supersede and go beyond, the psychoanalytic enterprise that our birthday boy set in motion. Why deny it?

Cross-posted to Long Sunday.For more, check out the naked gaze's "Obscene Images (1)".

And for other birthday tributes, see Harold Bloom's "Why Freud Matters", Paul Broks's "The Ego Trip", Will Hutton's "A time to celebrate, not denigrate, Freud", or Christina Patterson's "A Freud for all seasons". MotherPie offers some feminist commentary and a whole series of links. And here's Freud's last living patient.

Plus a site dedicated to the anniversary.

Then almost immediately I'll be off to Buenos Aires and Asunción.

Then almost immediately I'll be off to Buenos Aires and Asunción.