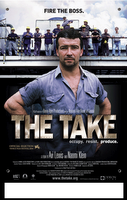

In Southern California for a conference, I finally got around to seeing Avi Lewis's and Naomi Klein's film The Take (official website here), which champions the Argentine movement to take over and recuperate abandoned factories.

In Southern California for a conference, I finally got around to seeing Avi Lewis's and Naomi Klein's film The Take (official website here), which champions the Argentine movement to take over and recuperate abandoned factories.Before the screening, I joked with some friends that the movie would most likely say more about Canada than about Argentina. But so indeed it turned out.

The Take gives us the Canadian dream: young, idealistic do gooders, who tell us they have for years lived with "tear gas by day, theory by night," spreading the word that an alternative is possible. Nothing revolutionary, mind you: merely the small difference of a slightly kinder, slightly more gentle capitalism.

Lewis and KIein are blithely unconcerned by the fact that the justification for the factory takeovers is presented very much in line with neoliberal rationality itself. We are told that worker-run businesses are more "efficient," because their workings are more transparent and because they have been cleansed of the corruption of their former owners. The state is warned not to intervene against the enterprising former workers, who show magnificent entrepreneurship as they lovingly care for and reactivate their sadly abandoned machines.

Obviously, no viewer can resist the banal liberal point that we'd rather see the workers Freddy and Lalo in charge of the plant than the Montgomery Burns style caricature of a former owner. But precisely the irresistability of this point is problematic.

And what's most striking is how much this is a film about affect, motivated by affect. You'd struggle hard to find a movie with more shots of men crying. The camera lingers on the tears rolling down their tough porteño cheeks. The men cry with nostalgia when they tour the ruined factory. They cry with joy when the provincial legislature gives them the legal right to return. They cry with frustration that their sense of self and masculine dignity has been humilliated, now they can no longer provide for their family (the wife's make up, the children's happy meals).

But finally, the film's closing sequence is a long montage of workers smiling, beaming, laughing in their pride and satisfaction as they joyfully invest their labour power into the production of value.

Simone Weil would have been pleased.

For they all worked happily ever after.

Update: tears revisited.

No comments:

Post a Comment