Gabriel García Márquez's "No One Writes to the Colonel" is concerned above all with tiredness and waiting--and so also the corresponding attitudes of the body. It provides, therefore, a version of what Deleuze terms the "time-image":

Gabriel García Márquez's "No One Writes to the Colonel" is concerned above all with tiredness and waiting--and so also the corresponding attitudes of the body. It provides, therefore, a version of what Deleuze terms the "time-image":the series of time. The daily attitude is what puts the before and after into the body, the body as the revealer of the deadline. The attitude of the body relates thought to time as to that outside which is infinitely further than the outside world" (189)The story opens with the colonel of the novella's title making his wife a cup of that ubiquitous stimulant, coffee, banishing tiredness with caffeine. The process is described in all its material determinants: the ground beans, the boiling fluid, and a series of containers that themselves leech into the resulting mixture as he "scrape[s] the inside of the can with a knife until the last scrapings of the ground coffee, mixed with bits of rust, fell into the pot" (109).

At the same time, we also get an early insight into the physical maladies that ail both the colonel and his wife. He finds his gut and stomach affected: "the colonel experienced the feeling that fungus and poisonous lilies were taking root in his gut" (109). She "had suffered an asthma attack" the previous night and "sip[s] her coffee in the pauses of her gravelly breathing. She was scarcely more than a bit of white on an arched, rigid spine" (109, 110).

The pair's deteriorating corporeal condition is a direct result of their long wait for the colonel's overdue pension. "For nearly sixty years--since the end of the last civil war--the colonel had done nothing else but wait" (109). And in the novella's sixty or so pages that follow, there is not much in the way of action except for the small routines that occupy the couple in their quiet, desperate poverty.

In the first few of these pages, the colonel makes coffee, winds the pendulum clock (one of their few remaining possessions, a constant reminder of time's passage), sees to the rooster they are keeping for a forthcoming cockfight, seeks out his suit, shaves, dresses... "He did each thing as if it were a transcendent act" (112). But of course these habits are far from transcendent; they are the endlessly iterated reflexes of a life spent waiting for transcendence, for a response from that department of state bureaucracy charged with allocating money to war veterans.

For of all the colonel's routines, the most symptomatic is his weekly trip down to greet the mail launch, follow the postman to the post office, and watch him sort the mail. "And, as on every Friday, he returned home without the longed-for letter" (127).

These are, then, bodies that have yet to be scripted into the national narrative. The colonel frequently and somewhat obsessively casts his mind back to his role in the revolution--in which ironically he himself was a type of mailman, whose own arduous journey delivering funds for the war is somewhat belated, arriving only "half an hour before the treaty was signed" (131). But he receives a receipt for his delivery, a proof of his service, and can't believe that it can now have been mislaid in the national archives. "'No official could fail to notice documents like those,' the colonel said" (131).

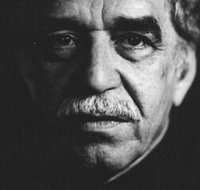

But indeed, despite the myriad documents and missives that circulate through the story--newspapers, pamphlets, an air-mail letter for the local doctor--the story emphasizes the lives and experiences that never achieve representation. All this writing is characterized by its absences, its lacks. The national papers are subject to censorship, demanding but also frustrating suspicious interpretation: "'What's in the news?' the colonel asked. [. . .] 'No one knows,' [the doctor] said. 'It's hard to read between the lines which the censor lets them print'" (119). While there's little hope that any outsiders will interest themselves in local happenings: "'To the Europeans, South America is a man with a mustache, a guitar, and a gun,' the doctor said, laughing over his newspaper. 'They don't understand the problems'" (127).

And though there are also clandestine missives and messages that attempt to make up for this representational lack, these endlessly say "the same as always," and the colonel doesn't even bother reading them (137).

Waiting, waiting, the colonel and his wife are subject to a "slow death" (165). But almost to the end, they maintain their patience, however much it is tried in their various squabbles as they figure out strategies to keep their bodies at least semi-nourished. Should they sell or keep the clock, and above all the rooster whose fight might lead to a big pay-out? "But suppose he loses," objects the wife (165).

In the end, the couple are reduced to something like what Giorgio Agamben terms "bare life". What are the two then to eat? And yet it is, strangely, this condition, in its loss of hope for transcendence and realization of pure, immanent materiality, that is portrayed as a moment of almost ecstatic ascesis. After all his hesitations, his anxiety, after all the ways in which he is ignored or taken advantage of by the state and local notables alike, somehow the waiting is over:

It had taken the colonel seventy-five years--the seventy-five years of his life, minute by minute--to reach this moment. He felt pure, explicit, invincible at the moment that he replied:(In the meantime, it would seem that García Márquez himself is now tired of writing.)

"Shit." (166)

No comments:

Post a Comment