Frank reads Edgar Allan Poe's 1845 short story "The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar", a text analyzed also by Roland Barthes and Jacques Derrida, in terms not merely of nineteenth-century enthusiasm for Mesmerism, but also an engagement with the (then) new communications technology of telegraphy.

The tale's narrator is some kind of amateur scientist, interested in Mesmerism, who is called to the deathbed of one M. Valdemar, eager to experiment as to whether hypnosis might delay or arrest "the encroachments of Death." The narrator successfully puts his patient in a trance, only to discover that he enters a sort of post-mortem limbo, in which his tongue, "swollen and blackened," displays a "strong vibratory motion" and a voice emanating as though "from a vast distance" declares "Yes; - no; - I have been sleeping - and now - now - I am dead."

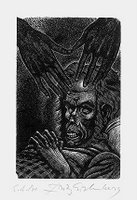

The tale's narrator is some kind of amateur scientist, interested in Mesmerism, who is called to the deathbed of one M. Valdemar, eager to experiment as to whether hypnosis might delay or arrest "the encroachments of Death." The narrator successfully puts his patient in a trance, only to discover that he enters a sort of post-mortem limbo, in which his tongue, "swollen and blackened," displays a "strong vibratory motion" and a voice emanating as though "from a vast distance" declares "Yes; - no; - I have been sleeping - and now - now - I am dead." General horror ensures, and Valdemar is left in his funereal trance for seven months. Then, as the narrator decides finally to awaken his patient, once more "the tongue quiver[s]" and a voice is heard intoning "For God's sake! - quick! - quick! - put me to sleep - or, quick! - waken me! - quick! - I say to you that I am dead!" "Waking" him, the narrator finds that, at one stroke, the body deteriorates, leaving only "a nearly liquid mass of loathsome - of detestable putrescence."

Frank reads this episode, of the tongue speaking from within a dead body, both as a scene of writing--a black mark on a face white as paper--and as an instance of telegraphic communication. The vibrating tongue functions as a vibrating armature, registering a voice transmitted from an almost unimaginable distance, and conveying with it the affect associated (for Poe) with the innovation, creativity, and novelty of the new technology.

In stressing the affective qualities of telegraphic communication, Frank sees Poe's story as staging an almost anticipatory criticism of the discourse of science and transparency that will soon claim telegraphy for its own:

The narrator's facts-in-the-case [cf. the story's title], antifigurative style can be understood as governed by a decontamination script, one that tries to purify itself of figurative language: the struggle between the narrator and Valdemar, a struggle over style, is more specifically a struggle over figure. [. . . The story can then be read as] a burlesque of the antifigurative style and its desire for a purified control. [. . .] Poe's writing insists not on telegraphy as antifigurative but on telegraphy as (from the start) an overdetermined figure for, precisely, effective or manipulative writing, writing that may conceal the figurative but can never do without it. (655-656)At the interface of telegraphic and literary writing, and also registering a nascent contest between and over these two technologies of communication, Poe's story is therefore profoundly political. At stake is

the control of body parts, thinking, and feeling of people at a distance [. . . that] creates the imagined possibility of a social body's consensus through the powerful force of a mass medium. (657)At stake, in other words, is the properly posthegemonic question of the affective technologies that produce the fantasy--the "imagined possibility"--of a consensus that will then be misread as hegemony. The alternative is perhaps a dissolution, a literal body without organs, that belies the suspended animation of the mesmerized subject conjured up by rational control.

Such a dissolution provokes intense disgust in the narrator, and "unwarranted popular feeling" in his addressees, but is for Valdemar himself "a matter neither to be avoided nor regretted."

No comments:

Post a Comment