For José Roberto Duque, it is still the state that's at issue. He describes a police murder: a raid on a house in a poor Caracas neighbourhood, the special forces storming up the stairs to their target, the body thrown out of the window, the witnesses coached to say the victim was a "bully, a delinquent," the falsified autopsy and death certificate. Everything conducted smoothly enough, an efficient exercise in limpieza, cleansing. People play along. "Nobody wants to get in trouble, right?" ("A Small Mistake" 123).

For José Roberto Duque, it is still the state that's at issue. He describes a police murder: a raid on a house in a poor Caracas neighbourhood, the special forces storming up the stairs to their target, the body thrown out of the window, the witnesses coached to say the victim was a "bully, a delinquent," the falsified autopsy and death certificate. Everything conducted smoothly enough, an efficient exercise in limpieza, cleansing. People play along. "Nobody wants to get in trouble, right?" ("A Small Mistake" 123).The problem, however, is the "small mistake" of the title: while the police are still conducting their operation their informed by panicked relatives that they have the wrong address. "No, sir. This is house number 20, but on Ricuarte Alley. La Vuelta del Mocho is about eight blocks up." The police response: "Ah, shit." But too late, because the bureaucratic machinery of law enforcement can't be halted so easily. After all, it operates according to its own logic, at some remove from reality. The drugs and weapons have already been planted. The original victim is infinitely replaceable; the objects of state repression are "whatever" victims, their individual names interchangeable and ultimately irrelevant. Due process and procedure can't be derailed by these small details of individual identification.

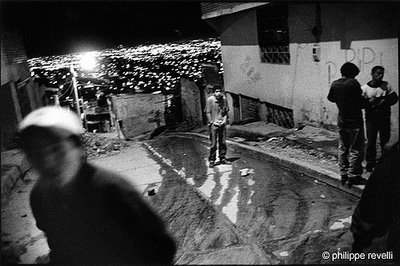

But this depersonalized, common object of state repression is also, in José Navia's piece from Bogotá's marginal urban slums, a common subject he terms the "multitude." And if for Duque the barrio is the site of random death, for Navia the multitude makes it also a place in which that institutionalized death drive faces the forces of life. The "rest of the city" slumbers while "a multitude begins to stir in the narrow, labyrinthine, unpaved alleys of Ciudad Bolívar" ("Ciudad Bolívar: Brush Strokes against Death" 125). Though "stigmatized by death" (125), the multitude are "youths on their feet, united, demanding a future, building a life [. . .] they invite life to be created in the place of death" (126).

Finally, however, Alberto Salcedo Ramos's vision is much darker. Here it's not so much the state versus the subaltern, margin lined up against the periphery, as an urban environment saturated by danger and violence. Mobility is no salvation, indeed it only invites further risk: "hailing a taxi on a Bogotá street at night--or even during the day--turns us into Russian roulette players." Salcedo Ramos goes on to suggest that "the only defensive manoeuver we have left is hoping, sometimes with ingeniousness, sometimes with arrogance, that the fatal shot doesn't hit us" ("The Drive-By Victim" 130). Of course, his perspective is partly that of the educated professional expressing the fear that his own city has become a no-go area in which any even semi-ostentatious display of privilege is pounced upon. He describes his experience being subject to a taxi-jacking, and describes himself as "a presumptuous animal that didn't know the laws of the jungle" (131).

Here again mistakes can be made, and here again those mistakes are somehow irrelevant: "If I wasn't rich but merely a poor copy, all the worse for me, not for them" (132). But the people who hold him up haven't quite made a mistake: he does after all have a savings account, he can after all procure money from a cash dispenser. And he has three cigarettes left, that the thieves can't pass up: "We smoke, too" (137).

But even Salcedo Ramos recognizes the sense of honour that runs through delinquency. It's a common trope, of course, of criminal society as equally, perhaps even more, rule-bound than the sovereign normality against which it rebels. "'We're thieves, man, not killers,' said the fat one, in a tone of offended dignity" (136). The middle classes have simply to learn this code of conduct, and abide by it. It's a world turned upside down, of course, but it has its logic. Salcedo Ramos ends up feeling grateful to his kidnappers, precisely because they maintained their calm and composure and stuck to their rulebook even as he himself tried to dodge and feint. When they release them he says "If I didn't shake their hands and invite them to breakfast the next day, it was because I wasn't brave enough. [. . .] And I thought that we are so screwed in this country that the only option left to us in the end is thanking the thieves" (137).

Isn't that because the country owes what little cohesion it has to the old-fashioned pragmatism of delinquency, so baldly opposed to the neoliberal state's mechanistic administration of bare life?

No comments:

Post a Comment