For a postcolonial society even to be envisaged, that society must be placed within historical time, and allocated both a destiny and an origin.

Benedict Anderson's point about the temporality of national consciousness is similar. Anderson writes that it is "the idea of a sociological organism moving calendrically through homogenous, empty time [that] is a precise analogue of the idea of the nation, which is also conceived as a solid community moving steadily down (or up) history" (Imagined Communities 26).

But where Anderson argues that this temporality is particular to the novel and the newspaper, and so to print capitalism, Carrera wants to show ways in which it was also visualized, depicted in the art as well as the literature of the nascent Spanish American republics.

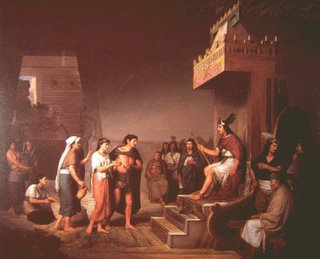

So whereas Anderson traces a shift from a medieval culture in which "the figuring of imagined reality was overwhelmingly visual and aural" (23) to the novel and the newspaper as "forms [that] provided the technical means for 're-presenting' the kind of imagined community that is the nation" (25), Carrera shows how the iconography of Empire was replaced with an alternative visual imagination specific to national self-determination. From "casta paintings" that map social hierarchy indelibly onto biology, to historical narratives of social invention such as José Obregón's The Discovery of Pulque.

Painters such as Obregón, then, contest the ways in which the art of Empire "laid out the static sociopolitical territory of the royal subject's body visually." They therefore "revise and transform the eighteenth-century political and social construction of the royal subject into that of the nationalist body" (19).

From a categorization of ideal types, as found in the casta paintings, in which each limb or organ of society should know its rightful place, to the historicization of identity as part of a dynamic social whole. Obregón takes the calcified representations of the indigenous, "remove[s] them from the present and place[s] them into an originating and allegorical time" (32).

Of course, the price that the indigenous pay is that, restored to history by the mestizo state, they are also marginalized and rendered invisible in the present.

No comments:

Post a Comment