By 1947, Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, Dolores del Rio, and Gene Raymond had already flown down to Rio, Basil Rathbone had escaped and gone on the rampage in Rio, even Charlie Chan had made it to Rio, while Jane Powell and Ann Southern would soon be on their way, Carmen Miranda in tow, though she'd already been there for at least a night with Don Ameche. Meanwhile, coming the other way, we'd had both a girl and a kid emerge from the Brazilian metropolis.

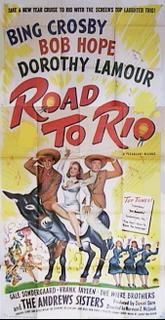

By 1947, Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, Dolores del Rio, and Gene Raymond had already flown down to Rio, Basil Rathbone had escaped and gone on the rampage in Rio, even Charlie Chan had made it to Rio, while Jane Powell and Ann Southern would soon be on their way, Carmen Miranda in tow, though she'd already been there for at least a night with Don Ameche. Meanwhile, coming the other way, we'd had both a girl and a kid emerge from the Brazilian metropolis.So by the time that Bing Crosby and Bob Hope get on the road to Rio, it's more a well-travelled expressway than a winding path.

Thanks to this slew of 1930s and 1940s movies, Rio de Janeiro was by now almost familiar to US cinema-goers. And it became familiar, as Latin America so often has, via its music, or a version of its music. Most of the films I've just mentioned are musicals, or contain musical interludes, often set in the city's opulent nightclubs, as Hollywood imagined them. Road to Rio is no exception, and can even afford to be self-reflexive about its trading in Latin musical exotica, as in the climactic wedding scene where Bob Hope hams up a parody version of Carmen Miranda.

But for all its familiarity, Rio maintains its distance. There's a dark side to Latin America in these films, though this touch of danger (touch of evil as Welles will soon suggest) is also part of its allure. Here that dangerous enticement is figured as hypnosis: the evil aunt, from whom Bing and Bob have to wrest the beautiful niece, keeps her charge in check by dangling her ever-present pendant in front of the girl's eyes and telling her that she's feeling sleepy... She pulls the same trick on our hapless heroes, almost (but not quite) inveigling them into shooting each other in a duel in the middle of what is, not insignificantly, the only bit of untamed nature we get to see.

But for all its familiarity, Rio maintains its distance. There's a dark side to Latin America in these films, though this touch of danger (touch of evil as Welles will soon suggest) is also part of its allure. Here that dangerous enticement is figured as hypnosis: the evil aunt, from whom Bing and Bob have to wrest the beautiful niece, keeps her charge in check by dangling her ever-present pendant in front of the girl's eyes and telling her that she's feeling sleepy... She pulls the same trick on our hapless heroes, almost (but not quite) inveigling them into shooting each other in a duel in the middle of what is, not insignificantly, the only bit of untamed nature we get to see.It's interesting, however, that Crosby and Hope's characters pick up on hypnosis as a technique to outwit the aunt's henchmen. Moreover, the movie ends with a scene in which Bob has himself subjected the girl to a marriage against her will by means of the same pendant once owned by the aunt. This mirroring or imitation is found throughout the film (and not just this one, it's worth adding). Indeed, Bing and Bob have already used a technique very similar to hypnosis in order to trick breakfast from a seasick liner passenger.

The imitation goes every which way: Hope parodies Miranda's (almost) self-parodic Americanized Brazilianism, while a trio of Brazilian musicians are passed off as part of a Dixie band by being taught the limited "hep cat" vocabulary of "You're telling me," "You're in the groove, Jackson," and "This is Murder."

And the film's best and catchiest number, the one instance of Crosby performing with the Andrews sisters on screen, is "You Don't Even Have to Know the Language", a celebration of affective tourism, the possibilities of immediate contact beneath discourse:

You stop at the Copacabana(Meanwhile, how about this for a song of good neighborliness?)

With the Sugar Loaf mountain in view

So the words on the menu mean nothing

You can't ask a soul what to do

But, you don't have to know the language

With the moon in the sky

And the girl in your arms

And a look in her eyes.

Despite all this, there remain inextricable obstacles to getting under the Latin skin. Some hard kernel of unknowable difference. Here, this is figured through the mysterious "papers" that drive the film's plot. We never figure out what they are. The film disappoints our expectations, self-reflectively denying us our full enjoyment of latinidad. The cavalry don't turn up in the end. And the papers? We don't get to read them, because fundamentally they must be illegible, an instance or trace some unbridgeable Latin American difference.

And so there's a strange, subterranean resonance here, between this lightest of comedic representations of Latin America, and that most traumatic and anguished view, Herzog's Aguirre, in which Ruy Guerra's Don Pedro de Ursúa dies still clutching some intractable, illegible fragment of the Latin American real...

(Crossposted from Latin America on Screen.)

No comments:

Post a Comment