Giovanni Arrighi's "Hegemony Unravelling 2" is, frankly, rather disappointing. I commented on "Hegemony Unravelling 1" in an earlier entry. This second installment continues the argument that US global dominance is in terminal decline, and compares the end of this particular capitalist "spatial fix" with the successive declines of Genoa, the United Provinces, and Great Britain, each of which anchored earlier "cycles of accumulation."

Unlike Hardt and Negri, however, who likewise claim that the current global system is shortly coming to an end, Arrighi believes that it will merely be superseded by a new system, this time with China in the driving seat: just as the US was the beneficiary of European wars in the first half of the twentieth century, so it is "China" that is "the real winner of the War on Terrorism" (115).

But as for "whether this 'victory' can translate into a new global spatial fix and what such a fix will look like" (115), Arrighi declines to elaborate. He has even less to say about the "less violent and more benevolent alternatives" that he invokes in his article's dying breath (116).

Meanwhile, of hegemony in the Gramscian sense of order secured through consent, all Arrighi adds is the notion that the US has, since Vietnam, moved from offering protection against real external threats to operating a "protection racket" that provides security only from threats (real or imagined) that it itself generates. Hence states such as Japan and Germany, acting as rational actors in the global game of fiscal and political trust, have withdrawn their support from US overseas adventures, leaving the global hegemon for the first time to shoulder the military, political, and economic costs of its imperial project: "the failure of George W. Bush to make US clients pay for the second Iraq war [. . .] can be taken as a sign that by then the United States had lost both hegemoney [i.e. the ability to extort tribute] and hegemony [i.e. legitimacy]" (112).

The rise and fall of empires obeys, for Arrighi, the logic of some profound universal and transhistorical set of laws. There's precious little room here for agency on the part either of the dominant or the dominated. Occasionally it is suggested that Bush's neoconversative team made mistakes, for instance by "pushing" the American protection racket "too far" (113), but really it hardly seems to matter as, Arrighi suggests, US decline is as inevitable as, in retrospect, was the sun setting on the British Empire a century or so ago.

And as for the notion that subalterns (the proletariat, the Third World, or whatever) might become historical actors: well, Arrighi seems to be saying, forget about it.

Thursday, September 29, 2005

Wednesday, September 28, 2005

technorati

[A rare, I hope, instance of me meta-blogging...]

Something very odd is going on with technorati.

I've been a little frustrated, as over a week ago it seems they stopped indexing this page, just when I was in the middle of retrospectively adding tags to previous posts. I wrote several emails to their support, but no answer.

And I've been keeping essentially all my posts on the front page here until technorati spiders come and index it--even though that breaks my feed.

It's all been a bit of a pain. Most of all, in that, in a fervor of thinking that this tag business was in fact a good thing (partly having been convinced of their worth by Brian Lamb of Abject Learning), I'd spent quite a while adding all those tags...

(I suspect that some algorithm had determined that so many new tags in such a short time meant that my blog was a spam blog; but 10 seconds looking at it should, one might have thought, have convinced a human observer otherwise...)

In further frustration, I cc-ed the last couple of my emails to David Sifry, technorati's founder and CEO. He wrote back and said he'd look into the problem personally. Which is kind of cool, but it would be easier on him if his minions were more efficient about responding to support queries.

Now, meanwhile, for a bunch of different tags that I've been using it's showing all the posts as having updated 21 hours ago. Check out mormons, say, or, most strangely of all, last100, a tag of my own creation (referring to a class I teach) that right now shows 8 empty entries, all apparently posted exactly 21 hours ago. Though others such as martin parr still don't show up, let alone, I'm especially sad to say, posthegemony.

I have no idea what's going on.

[Update: well, that bizarreness seems to have passed. But they still ain't indexing this blog... Oh, and there's still something odd with the tag last100.]

[Update: this is very close to being a story with a happy ending... The vast majority of my tags were indexed sometime overnight. Still problems with a few, however, that I have created: arrighi, indigenism, and new left review, for instance.]

[Update: and those tags are now fixed... Normal service to be resumed.]

Something very odd is going on with technorati.

I've been a little frustrated, as over a week ago it seems they stopped indexing this page, just when I was in the middle of retrospectively adding tags to previous posts. I wrote several emails to their support, but no answer.

And I've been keeping essentially all my posts on the front page here until technorati spiders come and index it--even though that breaks my feed.

It's all been a bit of a pain. Most of all, in that, in a fervor of thinking that this tag business was in fact a good thing (partly having been convinced of their worth by Brian Lamb of Abject Learning), I'd spent quite a while adding all those tags...

(I suspect that some algorithm had determined that so many new tags in such a short time meant that my blog was a spam blog; but 10 seconds looking at it should, one might have thought, have convinced a human observer otherwise...)

In further frustration, I cc-ed the last couple of my emails to David Sifry, technorati's founder and CEO. He wrote back and said he'd look into the problem personally. Which is kind of cool, but it would be easier on him if his minions were more efficient about responding to support queries.

Now, meanwhile, for a bunch of different tags that I've been using it's showing all the posts as having updated 21 hours ago. Check out mormons, say, or, most strangely of all, last100, a tag of my own creation (referring to a class I teach) that right now shows 8 empty entries, all apparently posted exactly 21 hours ago. Though others such as martin parr still don't show up, let alone, I'm especially sad to say, posthegemony.

I have no idea what's going on.

[Update: well, that bizarreness seems to have passed. But they still ain't indexing this blog... Oh, and there's still something odd with the tag last100.]

[Update: this is very close to being a story with a happy ending... The vast majority of my tags were indexed sometime overnight. Still problems with a few, however, that I have created: arrighi, indigenism, and new left review, for instance.]

[Update: and those tags are now fixed... Normal service to be resumed.]

Abigail's Party

There is no realm of "truth" underneath or distinguishable from the realm of "falsehood." There are no secrets to exhume. There are no psychological depths to mine–or at least none that matter–in Abigail's Party. No one is being deceitful. No one is covering up anything. That would simplify understanding. We could dive down and discover the truth as we do in films like Citizen Kane or Casablanca. The situation Leigh imagines–here and in all of his work–is far more complex. There is no escape from slippery, shifting, multivalent surfaces. There is no realm of unsullied, uninflected reality underneath. Everything is mixed. We must live in the flux....Indeed, it's the fact that everyone says what they think in this film that makes it so painful to watch. Which shows that this postideological flux has everything to do with affect (the barbs, the resentment, the worry, and the drunkenness of suburban social interaction) and habit (the pettiness, the gender roles, the classification by taste, and the drunkenness again).

Saturday, September 24, 2005

Popol Vuh

there is no longerThey conclude in similar vein:

a place to see it, a Council Book,

a place to see "The Light that Came from Beside the Sea,"

the account of "Our Place in the Shadows,"

a place to see "The Dawn of Life." (63)

This is enough about the Being of Quiché, given that there is no longer a place to see it. There is the original book and ancient writing owned by the lords, now lost. (198)The Popol Vuh itself, then, can only supplement or stand in for a lost or inaccessible text, a missing plenitude irrecoverable in the wake of Spanish conquest. Hence the ambivalence of the book's final lines, which assert either that this substitution has been successful in recapturing the lost history that it retells, or that the supplement can be no more than an epitaph to an independent existence now irredeemably extinguished: "everything has been completed here concerning Quiché, which is now named Santa Cruz" (198).

Something of this impossibility inheres in all subaltern texts: they recognize that the power of naming (a power continually underscored within the pages of the Popol Vuh) escapes their grasp. At best, the subaltern can hope to insinuate him or herself within the codes established by the dominant, perhaps to upset or relativize that discourse of power, at least slightly. At best, the subaltern aims at a precarious reinscription within or between the terms structuring the new doxa.

The Popol Vuh is a genealogy of the Quiché state, a record of its noble houses and lordships, and a celebration of its (former) power to exact tribute from surrounding tribes:

What they did was no small feat, and the tribes they conquered were not few in number. The tribute of Quiché came from many tribal divisions.The last lords in the list have Spanish names: Don Juan de Rojas and Don Juan Cortés. They themselves now pay tribute to the Spanish, rather than receiving it from their fellow indigenous people. Like many native aristocrats, however, Juan de Rojas and Juan Cortés sought accommodation with the Spaniards, hoping to maintain their rights to local domination under the aegis of European imperialism. And, as translator and editor Dennis Tedlock notes, the Popol Vuh itself may well have been a crucial implement in the case that the local lords made as they tried to establish dialogue with their new masters:

And the lords had undergone pain and withstood it; their rise to splendor had not been sudden. Actually it was Plumed Serpent who was the root of the greatness of the lordship.

Such was the beginning of the rise and growth of Quiché.

And now we shall list the generations of lords, and we shall also name the names of all these lords. (194)

Juan Cortés, whose duties as Keeper of the Reception House Mat would have included tribute collection had he served before the coming of [conquistador] Alvarado, worked constantly to restore tribute rights to the lordly lineages of the town of Quiché. In 1557 he went all the way to Spain to press his case, and it could be that he took a copy of the alphabetic Popol Vuh with him. (56)Interestingly, the subjugated tribes are described twice as a multitude, at least as they are ventriloquized by the scribal aristocrats of their subjugators: "Don't we constitute a multitude of people?" (166); "Aren't we a multitude?" (169).

The real absence, then, is surely not the defeated state nobility whose destruction these texts bemoan; it is rather the constituent power that they themselves repress, in a form of anticipatory counter-insurgency.

But what can we say of constituent power in pre-Columbian societies, when constituted power has so thoroughly mystified its origins in the few texts that are available to us?

Friday, September 23, 2005

families (Parr II)

The Presentation House Gallery has a great bookshop for photography titles. I picked up another Martin Parr book: From Our House to Your House.

This is a collection of home-made pictorial Christmas cards, from the 1930s to the 1990s. There is the usual cavalcade of outdated fashion, poor taste, and even worse humour. Families arrayed in their Sunday best, stiff and upright, or laboriously showing off their skills as performers or musicians. The 1979 card from "The Ritchie family": full colour, appalling clothes, dubious mantelpiece ornaments, porn-star moustaches. The 1980 card from Merrily and Dick Gifford, their children "Debbie, Deanna, Dick, Dan, Daurie, Ann, David, and Dicksie" all lined up by the side of the pool.

Most extraordinary, however, are the image manipulations. Often these entail distortions of scale: a family playing among outsize Christmas baubles, for instance. And there's a peculiar fascination with the notion of giant children who have their parents, literally, in the palm of their hands.

These cards (and their attendant Christmas letters) are the means by which American families presented themselves to the world, to their extended network of friends and acquaintances. But the cracks and faultlines within those families are also all too visible, all too painfully on show.

[Update: I note that Sydneysiders can see Martin Parr talk on October 8th.]

This is a collection of home-made pictorial Christmas cards, from the 1930s to the 1990s. There is the usual cavalcade of outdated fashion, poor taste, and even worse humour. Families arrayed in their Sunday best, stiff and upright, or laboriously showing off their skills as performers or musicians. The 1979 card from "The Ritchie family": full colour, appalling clothes, dubious mantelpiece ornaments, porn-star moustaches. The 1980 card from Merrily and Dick Gifford, their children "Debbie, Deanna, Dick, Dan, Daurie, Ann, David, and Dicksie" all lined up by the side of the pool.

Most extraordinary, however, are the image manipulations. Often these entail distortions of scale: a family playing among outsize Christmas baubles, for instance. And there's a peculiar fascination with the notion of giant children who have their parents, literally, in the palm of their hands.

These cards (and their attendant Christmas letters) are the means by which American families presented themselves to the world, to their extended network of friends and acquaintances. But the cracks and faultlines within those families are also all too visible, all too painfully on show.

[Update: I note that Sydneysiders can see Martin Parr talk on October 8th.]

Thursday, September 22, 2005

future

Colonial logic often suggests that the further one travels from the metropolis, the further one returns back to a semi-forgotten past.

The Commonwealth semi-periphery, for instance, is cast as a redoubt of mid-century English innocence. Writing in The Times, Arnie Wilson cites what he calls "that traditional Kiwi joke: 'We’re about to land in Auckland — please put your watches back 50 years.'" Victoria, British Columbia, has also been described in similar terms.

The Commonwealth semi-periphery, for instance, is cast as a redoubt of mid-century English innocence. Writing in The Times, Arnie Wilson cites what he calls "that traditional Kiwi joke: 'We’re about to land in Auckland — please put your watches back 50 years.'" Victoria, British Columbia, has also been described in similar terms.

In the periphery itself, travelers are apt to find Dickensian exploitation, feudal simplicity, Stone Age barbarism, or even prehistoric lost worlds, depending upon inclination.

Alejo Carpentier's The Lost Steps (Los pasos perdidos) is a classic narrative of this spatialization of time: its narrator has to undertake a tortuous journey through a maze of Amazonian waterways in his quest to find the origin of music, the primitive foundation of melody and rhythm. At each turn he peels back decades, centuries of time passed and forgotten by "civilized" man.

But, as Mary Louise Pratt shows in her reading of Alexander Von Humboldt's travel writings, precisely the same gesture positing the Third World as some primal past also frames it as the site from which the future will be born. If Latin America was "a primal world of nature, an unclaimed and timeless space [. . .] whose only history was the one about to begin," then it could also be envisaged as "point of origin for a future that starts now, and will rework that 'savage terrain'" (Imperial Eyes 126, 127).

It is because America is our past that it can be, in Hegel's famous words, "the land of the future, where, in the ages that lie before us, the burden of the World's History shall reveal itself."

For Pratt, it is Humboldt who most persuasively and influentially articulates this sense of the Americas as a continent pregnant with possibilities for investment and growth:

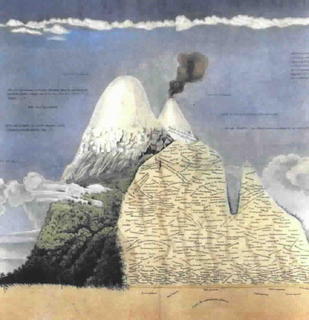

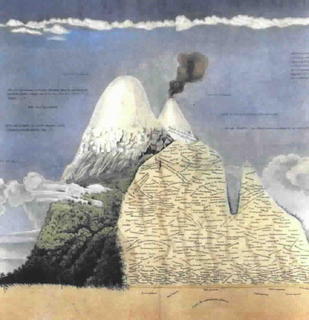

After all, doesn't Humboldt's sketch of Chimborazo resemble nothing so much as a nineteenth-century factory, complete with its innards dissected and delineated according to the natural division of labour, and its serrated roof topped by a chimney belching smoke into the blue sky?

Pratt quotes from the Preface to Humboldt's Personal Narrative, which predicts an age in which:

In the jungles of Latin America--and this is how its landscape differs from the English Lakes or French Alps beloved of other Romantics--affect is envisaged as combining with science and harnessed to capital in the name of a utopian future of industrial enrichment.

The Commonwealth semi-periphery, for instance, is cast as a redoubt of mid-century English innocence. Writing in The Times, Arnie Wilson cites what he calls "that traditional Kiwi joke: 'We’re about to land in Auckland — please put your watches back 50 years.'" Victoria, British Columbia, has also been described in similar terms.

The Commonwealth semi-periphery, for instance, is cast as a redoubt of mid-century English innocence. Writing in The Times, Arnie Wilson cites what he calls "that traditional Kiwi joke: 'We’re about to land in Auckland — please put your watches back 50 years.'" Victoria, British Columbia, has also been described in similar terms.In the periphery itself, travelers are apt to find Dickensian exploitation, feudal simplicity, Stone Age barbarism, or even prehistoric lost worlds, depending upon inclination.

Alejo Carpentier's The Lost Steps (Los pasos perdidos) is a classic narrative of this spatialization of time: its narrator has to undertake a tortuous journey through a maze of Amazonian waterways in his quest to find the origin of music, the primitive foundation of melody and rhythm. At each turn he peels back decades, centuries of time passed and forgotten by "civilized" man.

But, as Mary Louise Pratt shows in her reading of Alexander Von Humboldt's travel writings, precisely the same gesture positing the Third World as some primal past also frames it as the site from which the future will be born. If Latin America was "a primal world of nature, an unclaimed and timeless space [. . .] whose only history was the one about to begin," then it could also be envisaged as "point of origin for a future that starts now, and will rework that 'savage terrain'" (Imperial Eyes 126, 127).

It is because America is our past that it can be, in Hegel's famous words, "the land of the future, where, in the ages that lie before us, the burden of the World's History shall reveal itself."

For Pratt, it is Humboldt who most persuasively and influentially articulates this sense of the Americas as a continent pregnant with possibilities for investment and growth:

On the eve of Spanish American independence and the eve of a capitalist 'scramble for America' not unlike the scramble for Africa still to come, Humboldt's Views and his viewing stake out a new beginning of history in South America. (127)Humboldt's portrayal of the American landscape in terms of its dynamism, worked over by the "occult forces" of geology and climate, resonates as much with "industrialism and the machine age" as it does with the "spiritualist esthetics of Romanticism" (124). The region's immense forests, mountains, and plains constitute a natural factory: a complex mechanism characterized above all by its productivity.

After all, doesn't Humboldt's sketch of Chimborazo resemble nothing so much as a nineteenth-century factory, complete with its innards dissected and delineated according to the natural division of labour, and its serrated roof topped by a chimney belching smoke into the blue sky?

Pratt quotes from the Preface to Humboldt's Personal Narrative, which predicts an age in which:

the inhabitant of the banks of the Oroonoko will behold with extasy, that populous cities enriched by commerce, and fertile fields cultivated by the hands of freemen, adorn those very spots, where, at the time of my travels, I found only impenetrable forests, and inundated lands. (qtd. 131)And as she notes, in this description of an "ecstatic future counterpart" who will see the results of "rapturous nature" harnessed to industrial commerce (131, 130), Humboldt's discourse is ultimately affective. "Humboldt sought," Pratt tells us, "to pry affect away from autobiography and narcissism and fuse it with science" (124).

In the jungles of Latin America--and this is how its landscape differs from the English Lakes or French Alps beloved of other Romantics--affect is envisaged as combining with science and harnessed to capital in the name of a utopian future of industrial enrichment.

Wednesday, September 21, 2005

new left review

A satisfied customer writes...

I doubt anybody has been waiting with very bated breath for the second installment of my thoughts on Arrighi's "Hegemony Unravelling".

But I, at least, have been waiting for the relevant issue of the New Left Review. And as of yesterday it had yet to arrive.

I therefore emailed the NLR, asking if somehow my subscription had lapsed. They replied almost immediately telling me that no, I was paid up, promising to (re)send issue 33 straightaway, making efforts to ensure that delivery of issue 34 would be expedited, and informing me of the code by which I could access articles from their website.

It so happened, by strange coincidence, that today issue 33 finally turned up.

Still, full marks to the journal's subscription department for customer service.

So subscribe. You won't be left in the lurch.

I doubt anybody has been waiting with very bated breath for the second installment of my thoughts on Arrighi's "Hegemony Unravelling".

But I, at least, have been waiting for the relevant issue of the New Left Review. And as of yesterday it had yet to arrive.

I therefore emailed the NLR, asking if somehow my subscription had lapsed. They replied almost immediately telling me that no, I was paid up, promising to (re)send issue 33 straightaway, making efforts to ensure that delivery of issue 34 would be expedited, and informing me of the code by which I could access articles from their website.

It so happened, by strange coincidence, that today issue 33 finally turned up.

Still, full marks to the journal's subscription department for customer service.

So subscribe. You won't be left in the lurch.

Monday, September 19, 2005

parables

wood s lot points us to Jeremy Ravi Mumford's "The Inca Priest on the Mormon Stage", an interesting essay on Mormonism, nineteenth-century indigenism, and images of Inca society. Mumford shows how the early Mormon leader Brigham Young acted out his religion's claims to respectability through a performance of Incaism.

This in the context not merely of familiar elegies for the vanished noble savage, but a more particular construction of Inca society befitting US (and Mormon) self-imagination:

What struck me about Mumford's essay, however, is that there really is something to the comparison between Incas and Mormons, in this if no other regard: both are groups upon which social parables are played out with remarkable frequency.

Take Jon Krakauer's Under the Banner of Heaven, a book for which a murder in American Fork, Utah, provides the canvas on which to assay quasi-philosophical conjectures about "violent faith" and, indeed, the nature of life itself:

But Krakauer's book pales beside the granddaddy of them all, Norman Mailer's epic The Executioner's Song, which tracks the movement from petty thievery to careless murder to the point at which judicial execution became once again enshrined as apex of the American way of life (and death). Mailer shows how, despite the best efforts of liberal organizations such as the ACLU, Gary Gilmore summoned forth the new authoritarianism, a new "admirable order."

But Krakauer's book pales beside the granddaddy of them all, Norman Mailer's epic The Executioner's Song, which tracks the movement from petty thievery to careless murder to the point at which judicial execution became once again enshrined as apex of the American way of life (and death). Mailer shows how, despite the best efforts of liberal organizations such as the ACLU, Gary Gilmore summoned forth the new authoritarianism, a new "admirable order."

The thousand and more pages of Mailer's door-stopper cast this drama of, first, robbery and killing and, then, lawyering and killing, as "Eastern voices" responding to "Western voices."

And the West to which the East responds, the West that shapes the neo-conservative constitution of order through firing squad, electric chair, and lethal injection, is the West of Provo, Spanish Fork, and Salt Lake City, the West of Mormonism, the West to which Brigham Young led his people in transcontinental Exodus.

This in the context not merely of familiar elegies for the vanished noble savage, but a more particular construction of Inca society befitting US (and Mormon) self-imagination:

An Enlightenment revival of Hispanic scholarship had made English-speaking readers familiar with the Inca Empire as a profoundly alien society, yet one that was in many ways admirable. The Inca, according to much of this literature, were authoritarian in their politics but that authoritarianism produced admirable order and happiness. The success of Sheridan’s Pizarro in 1799 created a new wave of interest in the Incas among English speakers. The next year saw the publication of a children’s dialogue about the Incas, with lines such as: "Excellent people! Who can avoid respecting them?"Of course, it should come as no great surprise that the Incas have also been eulogized, not least by the great early twentieth-century Peruvian Marxist José Carlos Mariátegui, as incarnating a form of primitive Communism. Indeed, of all pre-Columbian societies, the Inca Empire offers most ideological malleability: I don't think that quite the same range of claims has been made for the Aztecs, for instance.

What struck me about Mumford's essay, however, is that there really is something to the comparison between Incas and Mormons, in this if no other regard: both are groups upon which social parables are played out with remarkable frequency.

Take Jon Krakauer's Under the Banner of Heaven, a book for which a murder in American Fork, Utah, provides the canvas on which to assay quasi-philosophical conjectures about "violent faith" and, indeed, the nature of life itself:

If I remain in the dark about our purpose here, and the meaning of eternity, I have nevertheless arrived at an understanding of a few more modest truths: Most of us fear death. Most of us yearn to comprehend how we got here, and why--which is to say, most of us ache to know the love of our creator. And we will no doubt feel that ache, most of us, for as long as we happen to live. (341)As befits a writer on mountaineering, Krakauer has long "yearned" to say something about death, violence, and sublimity, and it's in Mormonism that he feels he's found a suitable subject, whereas for instance the autobiographical reflections framing Into the Wild were rather forced onto a tale of Boy's Own anomie gone wrong.

But Krakauer's book pales beside the granddaddy of them all, Norman Mailer's epic The Executioner's Song, which tracks the movement from petty thievery to careless murder to the point at which judicial execution became once again enshrined as apex of the American way of life (and death). Mailer shows how, despite the best efforts of liberal organizations such as the ACLU, Gary Gilmore summoned forth the new authoritarianism, a new "admirable order."

But Krakauer's book pales beside the granddaddy of them all, Norman Mailer's epic The Executioner's Song, which tracks the movement from petty thievery to careless murder to the point at which judicial execution became once again enshrined as apex of the American way of life (and death). Mailer shows how, despite the best efforts of liberal organizations such as the ACLU, Gary Gilmore summoned forth the new authoritarianism, a new "admirable order."The thousand and more pages of Mailer's door-stopper cast this drama of, first, robbery and killing and, then, lawyering and killing, as "Eastern voices" responding to "Western voices."

And the West to which the East responds, the West that shapes the neo-conservative constitution of order through firing squad, electric chair, and lethal injection, is the West of Provo, Spanish Fork, and Salt Lake City, the West of Mormonism, the West to which Brigham Young led his people in transcontinental Exodus.

desire

I've posted some thoughts on desire and this strangest of Disney films over at Latin America on Screen.

Sunday, September 18, 2005

unconscious

Travel writer Tim Cahill tells us:

[UPDATE: OK, I've found one.]

Nor could one hope for a better example of the way in which the unconscious is cast in terms of (feminine) sexuality (and vice versa, of course): "sickly sweet odors," "moist darkness," "dank fecundity." Not that there is anything very unconscious about these associations for Cahill. A little later, in a shallow canyon high up on Mount Roraima, the plateau mountain that inspired Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World, he strips off his clothes and, standing "naked under the unfamiliar sun," informs us that "it seemed to me that the smooth, rounded, dripping rocks, the puddled depressions, the archways and spires, all had overtly sexual connotations." What follows is a patch of rather purple prose that ends with "a terrible roar of release" as water from the plateau cascades down the mountainside (56).

It is often suggested that psychoanalysis is complicit with the colonial imagination. But although (as a good Deleuzian) I'm skeptical of many aspects of Freud's work, it can also obviously be invoked to analyze and criticize colonialism's own fantasies and desires.

The thing about the unconscious is that it is at the same time both alien and strangely familiar, intimate: unheimlich. What is frightening about the unconscious is also what is frightening about the self.

Cahill admits that the Latin American landscape (its populace, too, while we're at it) functions for him as a kind of Rorschach blot: "there was a cavernlike quality to the canyon, and the mind does not allow such shapes to go uninterpreted" (55). But it is not as though such projections are "merely" imaginary. Or rather, the point is that they have real effects. As Cahill says of Conan Doyle's story, "his fantasy [. . .] was so compelling that it gave the area its name" (44). Moreover, Conan Doyle's fantasy motivates Cahill's own trip to the region, otherwise a wholly senseless enterprise, particularly at the time of year he is there:

And Cahill finds a fair few other foreigners who have either been adversely affected by this particular heart of darkness, or who were some way round the bend already. Not least the Latvian "hermit" Laime who "for nineteen years [. . .] had lived alone in the jungle, nineteen years alone with his thoughts" (48). But the prime example is Cahill, who is introduced as an anonymous third person, as though unrecognizable even to the author himself: "the gringo was sweating in the humid heat, and he began babbling in incoherent Spanish. [. . .] the big one with the beard, he was a writer named Tim Cahill" (40, 41).

The tropics, as so often, are a place where men (less often women) go to find themselves, to find the truth of the stories they heard as children, to find and confront their culture's primal fears. But they are also a place where outsiders too easily lose themselves, either figuratively or literally. The last person who had tried to climb the mountain in the rainy season was "a solitary hiker from Caracas who had supposedly died in the frigid rains there" (53). And Cahill and his friends dice with death at least twice, at the outset when they are stopped by a Venezuelan army patrol ("'They almost shot us,' I said, incredulous" [41]), and at the end when the pilot due to fly them back over Roraima crashes his plane on the way down to meet them.

Cahill ends his account with an image of the dead at Jonestown, whose story he had covered some years previously, and so an image of "all those bodies bloating in the heat and the rain" (59). The tragic end to the People's Temple saga, a tale of misplaced faith and mass suicide, comes to represent all the fears of what Latin America will bring out in us.

the jonestown report

I am frightened by the jungle. I am frightened by the sickly sweet odors, by the moist darkness, by the dank fecundity. I am frightened by the chaos: green things lash about in slow motion, choke off lesser plants, rise towards the sun like those subconscious horrors that sometimes bubble up into the conscious mind. (Jaguars Ripped My Flesh 42-43)He is writing about the rainforest of Northern Amazonia, more specifically the "Mundo Perdido" that straddles Venezuela and Guyana, and a clearer instance of Latin America as the West's unconscious would be hard to find.

[UPDATE: OK, I've found one.]

Nor could one hope for a better example of the way in which the unconscious is cast in terms of (feminine) sexuality (and vice versa, of course): "sickly sweet odors," "moist darkness," "dank fecundity." Not that there is anything very unconscious about these associations for Cahill. A little later, in a shallow canyon high up on Mount Roraima, the plateau mountain that inspired Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World, he strips off his clothes and, standing "naked under the unfamiliar sun," informs us that "it seemed to me that the smooth, rounded, dripping rocks, the puddled depressions, the archways and spires, all had overtly sexual connotations." What follows is a patch of rather purple prose that ends with "a terrible roar of release" as water from the plateau cascades down the mountainside (56).

It is often suggested that psychoanalysis is complicit with the colonial imagination. But although (as a good Deleuzian) I'm skeptical of many aspects of Freud's work, it can also obviously be invoked to analyze and criticize colonialism's own fantasies and desires.

The thing about the unconscious is that it is at the same time both alien and strangely familiar, intimate: unheimlich. What is frightening about the unconscious is also what is frightening about the self.

Cahill admits that the Latin American landscape (its populace, too, while we're at it) functions for him as a kind of Rorschach blot: "there was a cavernlike quality to the canyon, and the mind does not allow such shapes to go uninterpreted" (55). But it is not as though such projections are "merely" imaginary. Or rather, the point is that they have real effects. As Cahill says of Conan Doyle's story, "his fantasy [. . .] was so compelling that it gave the area its name" (44). Moreover, Conan Doyle's fantasy motivates Cahill's own trip to the region, otherwise a wholly senseless enterprise, particularly at the time of year he is there:

The urge to climb Mount Roraima in the rainy season is simply inexplicable without reference to psychiatric literature--and the tales of adventure one reads in childhood. (45)The notion that the tropics drive unwary travelers mad is a familiar one; but so is the idea that they must be a little unhinged to be there in the first place.

And Cahill finds a fair few other foreigners who have either been adversely affected by this particular heart of darkness, or who were some way round the bend already. Not least the Latvian "hermit" Laime who "for nineteen years [. . .] had lived alone in the jungle, nineteen years alone with his thoughts" (48). But the prime example is Cahill, who is introduced as an anonymous third person, as though unrecognizable even to the author himself: "the gringo was sweating in the humid heat, and he began babbling in incoherent Spanish. [. . .] the big one with the beard, he was a writer named Tim Cahill" (40, 41).

The tropics, as so often, are a place where men (less often women) go to find themselves, to find the truth of the stories they heard as children, to find and confront their culture's primal fears. But they are also a place where outsiders too easily lose themselves, either figuratively or literally. The last person who had tried to climb the mountain in the rainy season was "a solitary hiker from Caracas who had supposedly died in the frigid rains there" (53). And Cahill and his friends dice with death at least twice, at the outset when they are stopped by a Venezuelan army patrol ("'They almost shot us,' I said, incredulous" [41]), and at the end when the pilot due to fly them back over Roraima crashes his plane on the way down to meet them.

Cahill ends his account with an image of the dead at Jonestown, whose story he had covered some years previously, and so an image of "all those bodies bloating in the heat and the rain" (59). The tragic end to the People's Temple saga, a tale of misplaced faith and mass suicide, comes to represent all the fears of what Latin America will bring out in us.

Saturday, September 17, 2005

performativity

Another day, another Zorro movie. And Alain Delon's Zorro comes with a cheery theme song, courtesy of Oliver Onions. I defy you to listen to it (and you can find a clip here) and not feel, well, something. And the lyrics...

Another day, another Zorro movie. And Alain Delon's Zorro comes with a cheery theme song, courtesy of Oliver Onions. I defy you to listen to it (and you can find a clip here) and not feel, well, something. And the lyrics...Here's to you and meNow, c'mon, what more do you want?

Here's to being free

La la la laaa la la

Zorro's back.

This 1975 version takes the Zorro story from California and transports it to some generic tropical Latin American locale. The skies are blue, the nights are humid, the aristocrats and their servants are baroque and bewigged, the people are enslaved, and, yes, Zorro is back. Indeed, the sequence showing his arrival is splendid: in the middle of a scene taken directly from the 1920 Douglas Fairbanks movie, in which a priest is whipped for allegedly selling underweight goods, parallel edits show the dark figure of the masked avenger gradually coming into focus silhouetted against the azure sky. "Enough!" he declaims. "I want to show you what justice is."

Power is ever more centrally at issue in this version of the story. Power and its disguises. For here Zorro is the outcome of a double disguise: Alain Delon's character, Don Diego, whose real origin and role are murky, first stands in for the governor Miguel de la Serna, murdered at the outset by the dastardly Colonel Huerta, before he subsequently also transforms himself into the bandit with a conscience.

Don Diego therefore impersonates both legitimate power (as his Excellency the governor) and illegitimate counter-power (as the masked brigand). In both roles, however, he is restrained from violence by his promise to the dying de la Serna, in which he swore to uphold the good governor's ideals. Only in the climactic final scene, in which Huerta cold-bloodedly kills the (same) priest, Brother Francisco, to avert a social revolution, does Zorro feel that he is released from that promise. Huerta is duly despatched, albeit after a protracted fight sequence.

Then, in marked contrast with Tyrone Power's incarnation, Zorro rides off into the distance, leaving behind even his love interest, the fair (if somewhat ornery) Contessina Ortensia Pulido.

Then, in marked contrast with Tyrone Power's incarnation, Zorro rides off into the distance, leaving behind even his love interest, the fair (if somewhat ornery) Contessina Ortensia Pulido.This is, in short, a much less territorialized Zorro than either the 1920 or (particularly) the 1940 outings.

The fictional territory in which the action takes place is named either Nueva Aragon or Nuova Aragona: the movie is uncertain even as to its linguistic affiliations, and is dubbed into English from what could quite possibly have been a Babelic confusion of languages used on set. The colonial outpost depicted is an (almost) any-space-whatever of 70s exoticism: it might as well be Mozambique or Tangiers. (The very similar Burn! was in fact shifted during production from the Spanish Empire to the Portuguese.) What's important about the locale is that almost everything is out of place. This is a faux-European society imposed on the barren land of the Third World.

So no surprise that Zorro himself is very much a man of no fixed abode, a nomad who can only impersonate belonging. Here, almost everything is a matter of impersonation.

What's highlighted is the very ridiculousness of colonial society. In fact, this is a theme that underlies all Zorro films, however much at the same time they attempt to naturalize and legitimate the ideal of a benevolent imperialism.

What's highlighted is the very ridiculousness of colonial society. In fact, this is a theme that underlies all Zorro films, however much at the same time they attempt to naturalize and legitimate the ideal of a benevolent imperialism. The films derive their comedy from the antics of Don Diego as fop (here magnificently realized in a scene in which the governor rises from his throne to greet the visiting Pulidos only immediately to trip and fall headfirst on the ground). And Don Diego, in his uselessness, idleness, and futility, is always typical of the ruling colonial class. Which is why, after all, he has to become Zorro, i.e. to step outside that class, in order to reform it.

But whether incarnated in Zorro or Don Diego (here, impersonating governor Miguel de la Serna), what Delon's film more than any other underlines is the performativity of power.

[Meanwhile I note that Isabel Allende has written a Zorro novel. God help us all...]

(Crossposted from Latin America on Screen.)

Friday, September 16, 2005

smell

[See also Gilroy I and Gilroy II.]

Gilroy has been criticized for his "populist modernism" before, not least by Kobena Mercer, who took him to task as long ago as 1990 for his celebration of "black cultural practices that have 'spontaneously arrived at insights which appear in European traditions as the exclusive results of lengthy and lofty philosophical discussions'" ("Black Art and the Burden of Representation" 69). As we have seen in Postcolonial Melancholia, and as in all populisms, Gilroy wants to have his cake and eat it: both championing the spontaneous wisdom of the people and insisting on the intellectual's "fundamental" task of "education" ("Race and Faith Post 7/7"). Populism sets its store by the people but never fully trusts them, hence its characteristic double articulation of mobilization and demobilization. It puts its faith in the nation's ordinary common sense and sentiment, but at the same time seeks to exclude those who do not accord with its version of common sense, to mark them as somehow not fully part of that national community. Here, as so often, the rhetoric is directed primarily against political elites, specifically the New Labour government who have betrayed (Gilroy suggests) the faith conceded them by the 1997 electorate. But there is equal distrust of the cheap or petty, suburban or rural, "small-minded Englishness" (138) of those who are perhaps not "vulgar" or "ordinary" enough (67).

But surely the point of a truly Orwellian patriotism, if we really were to consider resurrecting this rather quaint project, is that you cannot pick and choose: true solidarity has to contend with the physicality and materiality of the most unpleasant of affects and habits. For Orwell, the politics of affect figured above all in the "physical repulsion" incarnated in the notion that "the lower classes smell." How, Orwell asks, can you have "affection for a man whose breath stinks--habitually stinks" (The Road to Wigan Pier 112)? Consensus or hegemony are not at issue here: Orwell points out that it is irrelevant how much "you may admire his mind and character." The point of conviviality is not the liberal politics of agreement, but the challenge of living together despite what is indeed an almost pre-political sensation of difference. "England," if an anti-racist patriotism has any sense at all, must belong to everyone. But of course at this point "England" also starts to fade, leaving only its increasingly marginal state apparatus, marginal despite its paroxysms of nervous violence, as in the killing of Jean Charles de Menezes at Stockwell. Yes, there will be points of historically-conditioned affective intensity (melancholia or shame, nostalgia or pride, anguish or joy), tied to images or sensations that are coded as national. And a television corporation or a cricket team, or even a government, might work within these codes to incite or dampen particular affective responses. But why should such overcoding also structure a politics of liberation?

Gilroy has been criticized for his "populist modernism" before, not least by Kobena Mercer, who took him to task as long ago as 1990 for his celebration of "black cultural practices that have 'spontaneously arrived at insights which appear in European traditions as the exclusive results of lengthy and lofty philosophical discussions'" ("Black Art and the Burden of Representation" 69). As we have seen in Postcolonial Melancholia, and as in all populisms, Gilroy wants to have his cake and eat it: both championing the spontaneous wisdom of the people and insisting on the intellectual's "fundamental" task of "education" ("Race and Faith Post 7/7"). Populism sets its store by the people but never fully trusts them, hence its characteristic double articulation of mobilization and demobilization. It puts its faith in the nation's ordinary common sense and sentiment, but at the same time seeks to exclude those who do not accord with its version of common sense, to mark them as somehow not fully part of that national community. Here, as so often, the rhetoric is directed primarily against political elites, specifically the New Labour government who have betrayed (Gilroy suggests) the faith conceded them by the 1997 electorate. But there is equal distrust of the cheap or petty, suburban or rural, "small-minded Englishness" (138) of those who are perhaps not "vulgar" or "ordinary" enough (67).

But surely the point of a truly Orwellian patriotism, if we really were to consider resurrecting this rather quaint project, is that you cannot pick and choose: true solidarity has to contend with the physicality and materiality of the most unpleasant of affects and habits. For Orwell, the politics of affect figured above all in the "physical repulsion" incarnated in the notion that "the lower classes smell." How, Orwell asks, can you have "affection for a man whose breath stinks--habitually stinks" (The Road to Wigan Pier 112)? Consensus or hegemony are not at issue here: Orwell points out that it is irrelevant how much "you may admire his mind and character." The point of conviviality is not the liberal politics of agreement, but the challenge of living together despite what is indeed an almost pre-political sensation of difference. "England," if an anti-racist patriotism has any sense at all, must belong to everyone. But of course at this point "England" also starts to fade, leaving only its increasingly marginal state apparatus, marginal despite its paroxysms of nervous violence, as in the killing of Jean Charles de Menezes at Stockwell. Yes, there will be points of historically-conditioned affective intensity (melancholia or shame, nostalgia or pride, anguish or joy), tied to images or sensations that are coded as national. And a television corporation or a cricket team, or even a government, might work within these codes to incite or dampen particular affective responses. But why should such overcoding also structure a politics of liberation?

Thursday, September 15, 2005

ressentiment

I've commented on this in passing before, but still can't quite understand why (some) people use their book's "Acknowledgements" as an opportunity to insist on their exclusion.

I say this after leafing through Stefan Meštrović's The Balkanization of the West, whose "Preface and Acknowledgements" end as follows:

Meštrović wants to portray himself as an unheeded prophet. He further tells us that his "colleagues in sociology" are "an especially mean-spirited lot" (xi), and so presumably especially disinclined to heed a prophet such as himself.

While I recognize the impulse to settle old scores, such protestations of hard-done-by rejection in the acknowlegements of a published work are surely at best petty, and at worst cast a shade over what is to follow.

Having said all that, Gustavo Pérez Firmat achieves his purpose with some wit and panache. From Life on the Hyphen:

I say this after leafing through Stefan Meštrović's The Balkanization of the West, whose "Preface and Acknowledgements" end as follows:

In the interest of the historical record, I wish to conclude this preface by listing the publications that rejected essays authored by me that I eventually incorporated into this book. (xiii)Meštrović goes on also to quote from the President-elect of the American Sociological Association's rejection of a proposed ASA session on the Balkan War (xiii-xiv).

Meštrović wants to portray himself as an unheeded prophet. He further tells us that his "colleagues in sociology" are "an especially mean-spirited lot" (xi), and so presumably especially disinclined to heed a prophet such as himself.

While I recognize the impulse to settle old scores, such protestations of hard-done-by rejection in the acknowlegements of a published work are surely at best petty, and at worst cast a shade over what is to follow.

Having said all that, Gustavo Pérez Firmat achieves his purpose with some wit and panache. From Life on the Hyphen:

I would also like to thank my colleagues in the Department of Romance Studies at Duke University for creating a work environment that made it much easier for me to stay home and write.

corruption

Tyrone Power's Zorro fights for family honour and the restoration of benevolent patriarchy.

Tyrone Power's Zorro fights for family honour and the restoration of benevolent patriarchy.Unlike Douglas Fairbanks's 1920 version, the 1940 remake depicts Empire, centre as well as periphery: the film opens with the young Diego de la Vega in Madrid, before he is called home to California. Spain, however, is in this portrayal some kind of cross between finishing school and holiday camp. There's little sense that the colonial enterprise is a matter of economic and political power relations. Empire, in short, is not here seen as a problem.

What is problematic is when Empire is subject to corruption.

For The Mark of Zorro, colonialism can and should be essentially pacific. Diego tells his fellow "young blades" busy learning "the fine and fashionable art of killing" that nothing happens in California: it is a land, he reports, of "gentle missions, happy peons, sleeping caballeros, and everlasting boredom." There "a man can only marry, raise fat children, and watch his vineyards grow."

But on returning, Diego discovers that this idyllic somnolence has been disturbed, as his father the alcalde has been overthrown and in his place is installed the avaricious pretender Don Luis Quintero with Captain Esteban Pasquale serving as his vicious sidekick. Lear-like, Diego's father Don Alejandro Vega has been humiliated, dispossessed, and subject to internal exile. The son therefore masquerades as the avenging Zorro in order to reinstall his emasculated progenitor.

Zorro's violence (and he is violent in a way that Fairbanks's character never is, killing his nemesis Pasquale with very little compunction indeed) is, as Julian Savage also argues, restorative rather than revolutionary. It's a displaced violence, performed by the prodigal son rather than the father himself, so absolving the virtuous patriarch, who refuses to take up arms, of any taint of coercion.

Zorro's violence (and he is violent in a way that Fairbanks's character never is, killing his nemesis Pasquale with very little compunction indeed) is, as Julian Savage also argues, restorative rather than revolutionary. It's a displaced violence, performed by the prodigal son rather than the father himself, so absolving the virtuous patriarch, who refuses to take up arms, of any taint of coercion.With his father back as mayor, Diego can finally settle down with his new-found wife, to raise his own fat children and watch his own vineyards grow--though one presumes that they don't grow far without some input from the "happy peons" and their labour power.

California, in short, and the Los Angeles in which the film's action is specifically set, can return to being the California familiar from so much Hollywood output of this period: a place of relaxation and leisure, natural fertility and good living, fortunately somewhat removed from world events. Oh, and underpinned by unacknowledged Latino labour.

It would not be long, though, before Power himself would have to gird up his fighting loins, first putting Hollywood on a war footing in an early World War II propaganda film, and then transforming himself from indolent matinée idol to man of war.

It would not be long, though, before Power himself would have to gird up his fighting loins, first putting Hollywood on a war footing in an early World War II propaganda film, and then transforming himself from indolent matinée idol to man of war.All very inspiring, no doubt. But why should we imagine that Hollywood either before or after the war was so very free from corruption?

(Crossposted from Latin America on Screen.)

Wednesday, September 14, 2005

ethics

As an addendum to my previous post:

So what about ethics? Ethics as post-political politics?

I'm not sure about the advantages of this move. I used to be. No longer.

So what about ethics? Ethics as post-political politics?

I'm not sure about the advantages of this move. I used to be. No longer.

representation

Commenting on my earlier post about global citizenship, Jodi argues that "politics is impossible without representation, that is, without drawing lines, making distinctions, exclusions, and representing these in terms of a universal."

And Craig half agrees when he says that he "can't imagine a politics without representations or symbols." He half disagrees, however, in that he argues that "it isn't clear that this has to be 'universal' such that the representation entirely overwhelms the original political moment of getting together and coming up with a project in common."

What's at issue here is perhaps partly the distinction between representation as proxy (Vertretung) and as portrait (Darstellung).

But to put it this way: why does what Craig terms a "point of a agreement" have to be symbolically portrayed? Why should agreement not be incarnated in the bodies that meet in an encounter or community? Isn't that what a politics of affective resonance suggests?

To conceive of politics only in terms of representation is surely a drastic limitation of its proper sphere. And yes, it may be the imposition of such limits that is, in Jodi's sense, the political. But the price paid is that politics is always secondary, always a delicate flower that can be interrupted at any moment.

I can see a certain sense to this position, but it casts the interruption itself into the outer darkness of anti-politics.

To put it another way: tonight I am giving a talk (on piracy) to a seminar on "political violence." I have been frustrated with this seminar in that so far we may sometimes have managed to discuss politics, and less often to discuss violence, but we have never managed to think through the conjuncture that would be "political violence."

Surely that's because, for a concept of politics founded in representation, violence has to be the anti-political rupture par excellence. But what a setback, no longer to be able to talk about violence politically, except as the other or limit to politics!

Yes, piracy pervades Western cultural and political imagination, and so (symbolic) representation. And, yes, that imagination casts pirates themselves into the outer darkness of anti-politics, villains of all nations, outcasts at sea. Their exclusion is one of the founding acts of the West's political representation: pirates have no proxies. But can we not conceive of pirates, too, as political subjects?

Or can pirates only become political by accepting our norms of liberal civility, representation, and mediation? By, already, agreeing with us?

And Craig half agrees when he says that he "can't imagine a politics without representations or symbols." He half disagrees, however, in that he argues that "it isn't clear that this has to be 'universal' such that the representation entirely overwhelms the original political moment of getting together and coming up with a project in common."

What's at issue here is perhaps partly the distinction between representation as proxy (Vertretung) and as portrait (Darstellung).

But to put it this way: why does what Craig terms a "point of a agreement" have to be symbolically portrayed? Why should agreement not be incarnated in the bodies that meet in an encounter or community? Isn't that what a politics of affective resonance suggests?

To conceive of politics only in terms of representation is surely a drastic limitation of its proper sphere. And yes, it may be the imposition of such limits that is, in Jodi's sense, the political. But the price paid is that politics is always secondary, always a delicate flower that can be interrupted at any moment.

I can see a certain sense to this position, but it casts the interruption itself into the outer darkness of anti-politics.

To put it another way: tonight I am giving a talk (on piracy) to a seminar on "political violence." I have been frustrated with this seminar in that so far we may sometimes have managed to discuss politics, and less often to discuss violence, but we have never managed to think through the conjuncture that would be "political violence."

Surely that's because, for a concept of politics founded in representation, violence has to be the anti-political rupture par excellence. But what a setback, no longer to be able to talk about violence politically, except as the other or limit to politics!

Yes, piracy pervades Western cultural and political imagination, and so (symbolic) representation. And, yes, that imagination casts pirates themselves into the outer darkness of anti-politics, villains of all nations, outcasts at sea. Their exclusion is one of the founding acts of the West's political representation: pirates have no proxies. But can we not conceive of pirates, too, as political subjects?

Or can pirates only become political by accepting our norms of liberal civility, representation, and mediation? By, already, agreeing with us?

Tuesday, September 13, 2005

transition

The superhero as double is common in Hollywood cinema. When he is not out saving the world, Superman takes refuge in his alter ego, the mild-mannered reporter Clark Kent. Batman is (and is not) the playboy Bruce Wayne. Spiderman and nerdy Daily Bugle photographer Peter Parker are one and (almost) the same.

But before all these (indeed, anticipating them by twenty years) there was Zorro aka Don Diego de la Vega. As the Zorro Legend website points out, Johnston McCulley's character, part foppish aristocrat, part avenging swordsman, echoes the Baroness Orczy's Scarlet Pimpernel. In The Mark of Zorro, Douglas Fairbanks takes this literary doppelganger and makes of him what could well be Hollywood's first superhero.

But before all these (indeed, anticipating them by twenty years) there was Zorro aka Don Diego de la Vega. As the Zorro Legend website points out, Johnston McCulley's character, part foppish aristocrat, part avenging swordsman, echoes the Baroness Orczy's Scarlet Pimpernel. In The Mark of Zorro, Douglas Fairbanks takes this literary doppelganger and makes of him what could well be Hollywood's first superhero.

(William Stoddard also has a good review and discussion of McCulley's book and the 1920 adaptation.)

Zorro's remit, however, is more local and more clearly political than that of most later superheroes. He's not called in to save the world, but he does aim to change it. Lately returned from Spain to his native California, Don Diego is disgusted with the corruption of Spanish imperial power, a corruption manifest in mistreatment of Indians, of priests, and (what is worst of all) of the beautiful Señorita Lolita Pulido.

Zorro's remit, however, is more local and more clearly political than that of most later superheroes. He's not called in to save the world, but he does aim to change it. Lately returned from Spain to his native California, Don Diego is disgusted with the corruption of Spanish imperial power, a corruption manifest in mistreatment of Indians, of priests, and (what is worst of all) of the beautiful Señorita Lolita Pulido.

Zorro's task is to rouse what has become a servile and languid creole aristocracy, and to goad them into ejecting the Spanish interloper from their shores.

Clearly, persuasion alone is not going to galvanize the Californian caballeros. Zorro aims to shame his fellows into action. The split between Don Diego, the fop rejected by the beauty Lolita, and Zorro, the dark knight who charms and impresses her with his hyper-masculine sword-thrusts, enacts the sexualized psychodrama of a quiescent upper class being beaten to the prize by new, mobile men of action. The lesson to be learned is immediately affective: the creole class lacks intensity; but shame could lead to revivified pride, and so to political significance at last.

The two aspects to Fairbanks's character are therefore less different psychologically than they incarnate differing states of the body: tiredness vs. wakefulness; langour vs. vigilance; passivity vs. activity; quiescence vs. tumescence. And the film as a whole is a film of the transition, of the individual but also the collective shift from sedentariness to motility.

Fairbanks's stunts (most of which he performed himself) are always exaggeratedly physical: his body describes ever more impressive arcs and leaps, jumping on to and over horses, over wagons and up walls. His characteristic movement is something like a sideways combined twist and turn and spring from a standing start.

At the same time, Zorro knows when to keep still. A favoured trick is to hide behind a bush, a door, or a wall, while a horde of pursuers blunder blindly past. It is not therefore movement per se that is valorized: it is the right combination of movement and rest. Zorro's stillness is taught with the alert possibility of sudden movement at any moment. His body is a spring coiled and ready to leap. It is the instant of contraction before an explosive power is unleashed.

Just a couple of decades after the US had dispossessed Spain of its last imperial possessions (Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines), and a couple of years after Europe had been suicidally bogged down in the First World War trenches, surely Zorro could also be seen as the image of US power ready to unfold. And his warning to Don Diego seen as a caution against the country's resting on its new-found laurels. Fairbanks's Zorro marks America's transition as it becomes superpower.

(Crossposted from Latin America on Screen.)

But before all these (indeed, anticipating them by twenty years) there was Zorro aka Don Diego de la Vega. As the Zorro Legend website points out, Johnston McCulley's character, part foppish aristocrat, part avenging swordsman, echoes the Baroness Orczy's Scarlet Pimpernel. In The Mark of Zorro, Douglas Fairbanks takes this literary doppelganger and makes of him what could well be Hollywood's first superhero.

But before all these (indeed, anticipating them by twenty years) there was Zorro aka Don Diego de la Vega. As the Zorro Legend website points out, Johnston McCulley's character, part foppish aristocrat, part avenging swordsman, echoes the Baroness Orczy's Scarlet Pimpernel. In The Mark of Zorro, Douglas Fairbanks takes this literary doppelganger and makes of him what could well be Hollywood's first superhero.(William Stoddard also has a good review and discussion of McCulley's book and the 1920 adaptation.)

Zorro's remit, however, is more local and more clearly political than that of most later superheroes. He's not called in to save the world, but he does aim to change it. Lately returned from Spain to his native California, Don Diego is disgusted with the corruption of Spanish imperial power, a corruption manifest in mistreatment of Indians, of priests, and (what is worst of all) of the beautiful Señorita Lolita Pulido.

Zorro's remit, however, is more local and more clearly political than that of most later superheroes. He's not called in to save the world, but he does aim to change it. Lately returned from Spain to his native California, Don Diego is disgusted with the corruption of Spanish imperial power, a corruption manifest in mistreatment of Indians, of priests, and (what is worst of all) of the beautiful Señorita Lolita Pulido.Zorro's task is to rouse what has become a servile and languid creole aristocracy, and to goad them into ejecting the Spanish interloper from their shores.

Clearly, persuasion alone is not going to galvanize the Californian caballeros. Zorro aims to shame his fellows into action. The split between Don Diego, the fop rejected by the beauty Lolita, and Zorro, the dark knight who charms and impresses her with his hyper-masculine sword-thrusts, enacts the sexualized psychodrama of a quiescent upper class being beaten to the prize by new, mobile men of action. The lesson to be learned is immediately affective: the creole class lacks intensity; but shame could lead to revivified pride, and so to political significance at last.

The two aspects to Fairbanks's character are therefore less different psychologically than they incarnate differing states of the body: tiredness vs. wakefulness; langour vs. vigilance; passivity vs. activity; quiescence vs. tumescence. And the film as a whole is a film of the transition, of the individual but also the collective shift from sedentariness to motility.

Fairbanks's stunts (most of which he performed himself) are always exaggeratedly physical: his body describes ever more impressive arcs and leaps, jumping on to and over horses, over wagons and up walls. His characteristic movement is something like a sideways combined twist and turn and spring from a standing start.

At the same time, Zorro knows when to keep still. A favoured trick is to hide behind a bush, a door, or a wall, while a horde of pursuers blunder blindly past. It is not therefore movement per se that is valorized: it is the right combination of movement and rest. Zorro's stillness is taught with the alert possibility of sudden movement at any moment. His body is a spring coiled and ready to leap. It is the instant of contraction before an explosive power is unleashed.

Just a couple of decades after the US had dispossessed Spain of its last imperial possessions (Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines), and a couple of years after Europe had been suicidally bogged down in the First World War trenches, surely Zorro could also be seen as the image of US power ready to unfold. And his warning to Don Diego seen as a caution against the country's resting on its new-found laurels. Fairbanks's Zorro marks America's transition as it becomes superpower.

(Crossposted from Latin America on Screen.)

Monday, September 12, 2005

hubris

In his Seven Theses on the Dinosaur, W. J. T. Mitchell argues that the dinosaur "symbolizes the power of the total state in its modern constitutional form." And Gabriela Nouzeilles has shown how the Argentine state invoked Patagonian dinosaur remains to naturalize its claims of national autonomy and power.

But the creatures in Harry Hoyt's classic silent The Lost World are a little more ambivalent.

Located in the heart of deepest, darkest Latin America, far up the Amazon somewhere at the confluence of Brazil, Colombia, and Peru, they certainly instantiate peripheral under-development.

Moreover, these lumbering beasts occupy what is merely one end of a continuum: they share their plateau homeland with both apes and rather menacing apemen. Down below, in the tropical jungle, are snakes, alligators, sloths, and human "half-breeds," the zambo half black, half Indian. Also left behind in camp, while the main exploring party go on above to search for signs of the previous expedition in the area, is Austin, an English domestic servant. The main party itself is divided between the old and more or less unfit (Professor Summerlee) and the young and nubile, not least the journalist Malone who proves his worth as a husband by braving the South American wilderness, so winning Paula White as female prize from the veteran explorer Sir John Roxton.

Moreover, these lumbering beasts occupy what is merely one end of a continuum: they share their plateau homeland with both apes and rather menacing apemen. Down below, in the tropical jungle, are snakes, alligators, sloths, and human "half-breeds," the zambo half black, half Indian. Also left behind in camp, while the main exploring party go on above to search for signs of the previous expedition in the area, is Austin, an English domestic servant. The main party itself is divided between the old and more or less unfit (Professor Summerlee) and the young and nubile, not least the journalist Malone who proves his worth as a husband by braving the South American wilderness, so winning Paula White as female prize from the veteran explorer Sir John Roxton.

But this hierarchy is not entirely stable: Jocko, the pet monkey, is (as Summerlee is reminded) more useful than some of the human members of the group; and Professor Challenger himself often (as Deleuze and Guattari point out) appears half-simian, hirsute and hot-headed, becoming-animal in his enthusiasm and stubbornness, and, not least, his vitriol against the written word.

Moreover, if the Conan Doyle novel on which the movie is based frames Challenger's expedition as a civilising mission, concluding with the apemen wiped out or enslaved and a client regime of grateful natives installed on the plateau, the film version differs sharply. Here, the "lost world" is devastated by a sudden volcanic eruption. One brontosaurus, however, escapes and is taken back to London--only there to escape again, cause mayhem in the streets, and collapse the iconic Tower Bridge, before, in the film's final frames, heading back towards Latin America by sea.

At the head of the tradition of monster movies that it initiates (animator Willis O'Brien would go on to work on King Kong, in many ways a remake of this film), The Lost World introduces a preoccupation with the monster as a genie disturbed, its vengeance a return for modern hubris. In this, of course, Spielberg's own Lost World is a true inheritor.

But if Spielberg's emphasis is on the dangers of science over-reaching itself, is not Harry Hoyt's theme imperial decline, his fear (and the fear radiated in the innumerable close-up reaction shots of Bessie Love playing Paula White) that of the untamed forces of what was once thought natural terrain for colonial intervention?

(Crossposted from Latin America on Screen.)

But the creatures in Harry Hoyt's classic silent The Lost World are a little more ambivalent.

Located in the heart of deepest, darkest Latin America, far up the Amazon somewhere at the confluence of Brazil, Colombia, and Peru, they certainly instantiate peripheral under-development.

Moreover, these lumbering beasts occupy what is merely one end of a continuum: they share their plateau homeland with both apes and rather menacing apemen. Down below, in the tropical jungle, are snakes, alligators, sloths, and human "half-breeds," the zambo half black, half Indian. Also left behind in camp, while the main exploring party go on above to search for signs of the previous expedition in the area, is Austin, an English domestic servant. The main party itself is divided between the old and more or less unfit (Professor Summerlee) and the young and nubile, not least the journalist Malone who proves his worth as a husband by braving the South American wilderness, so winning Paula White as female prize from the veteran explorer Sir John Roxton.

Moreover, these lumbering beasts occupy what is merely one end of a continuum: they share their plateau homeland with both apes and rather menacing apemen. Down below, in the tropical jungle, are snakes, alligators, sloths, and human "half-breeds," the zambo half black, half Indian. Also left behind in camp, while the main exploring party go on above to search for signs of the previous expedition in the area, is Austin, an English domestic servant. The main party itself is divided between the old and more or less unfit (Professor Summerlee) and the young and nubile, not least the journalist Malone who proves his worth as a husband by braving the South American wilderness, so winning Paula White as female prize from the veteran explorer Sir John Roxton.But this hierarchy is not entirely stable: Jocko, the pet monkey, is (as Summerlee is reminded) more useful than some of the human members of the group; and Professor Challenger himself often (as Deleuze and Guattari point out) appears half-simian, hirsute and hot-headed, becoming-animal in his enthusiasm and stubbornness, and, not least, his vitriol against the written word.

Moreover, if the Conan Doyle novel on which the movie is based frames Challenger's expedition as a civilising mission, concluding with the apemen wiped out or enslaved and a client regime of grateful natives installed on the plateau, the film version differs sharply. Here, the "lost world" is devastated by a sudden volcanic eruption. One brontosaurus, however, escapes and is taken back to London--only there to escape again, cause mayhem in the streets, and collapse the iconic Tower Bridge, before, in the film's final frames, heading back towards Latin America by sea.

At the head of the tradition of monster movies that it initiates (animator Willis O'Brien would go on to work on King Kong, in many ways a remake of this film), The Lost World introduces a preoccupation with the monster as a genie disturbed, its vengeance a return for modern hubris. In this, of course, Spielberg's own Lost World is a true inheritor.

But if Spielberg's emphasis is on the dangers of science over-reaching itself, is not Harry Hoyt's theme imperial decline, his fear (and the fear radiated in the innumerable close-up reaction shots of Bessie Love playing Paula White) that of the untamed forces of what was once thought natural terrain for colonial intervention?

(Crossposted from Latin America on Screen.)

Sunday, September 11, 2005

smoke

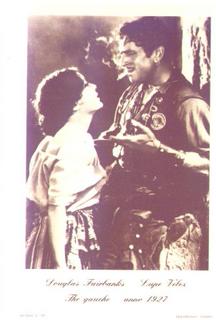

The original programme notes to The Gaucho, while emphasizing the painstaking research that lies behind the film's script and scenography, state that:

The original programme notes to The Gaucho, while emphasizing the painstaking research that lies behind the film's script and scenography, state that:Douglas [Fairbanks] has always held that "things as they are" are never as appealing as "things as we would like to see them."But what then does this film indicate about what its audience would like to see?

The answer would appear to be: miracles, shrines, macho Argentine country-folk, Lupe Velez's heaving bosom, and the power of religion to redeem even the most inveterate of criminals.

Meanwhile, we would like to see gauchos, if Douglas Fairbanks's portrayal is anything to go by, as raucous, rambunctious folk, who like to drink, dance, and fight, are athletic and a hit with the ladies, and who smoke like a chimney. Fairbanks's cigarette is his constant prop. At one point he swallows it up within his mouth while he pauses to kiss Velez, the mountain girl, only for it to pop out again shortly afterwards.

As always, however, the gauchos are a dying breed. (And it ain't just the lung cancer that'll get 'em.)

Though this film portrays them at their peak, overwhelming Andean villages and evil dictatorial usurpers alike, it also shows the gaucho tamed. Struck by a dreaded lurgy (the "black doom"), a mysterious illness that makes his hand black and numb, Fairbanks's un-named gaucho is about to commit suicide until the saintly girl of the shrine leads him to where Mary Pickford (playing the Virgin Mary) can cure him and turn his life around. Converted to Christianity, he determines to make an honest woman of his lover, Velez, and so presumably an honest, no longer gaucho, man of himself.

The Gaucho was touted for its lavish and expansive sets. The Andes here are near vertical cliffs, within which the people live in no more than caves. The plains, on the other hand, are bedecked with palm trees and throng with cattle for as far as the eye can see.

But who tends these cattle? Hardly anyone here works. Aside from the bartender in the village cantina and the padre at the shrine, the people are divided into three roughly equal parts: beggars, soldiers, and bandits.