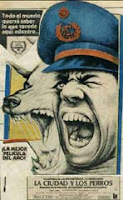

Francisco Lombardi's La ciudad y los perros is an adaptation of Mario Vargas Llosa's first book. The title translates as "The City and the Dogs" (though for some reason the book was translated into English as The Time of the Hero). But the film shows much less of the city and much more of the dogs than does Vargas Llosa's novel, whose first edition came complete with a map of Lima. Lombardi keeps us mostly within the claustrophobic confines of the military academy in which the "dogs," the army cadets, have forged a rough and tumble community whose hierarchies, values, and abuses both challenge and mirror those of the army, and by extension the nation, itself.

Francisco Lombardi's La ciudad y los perros is an adaptation of Mario Vargas Llosa's first book. The title translates as "The City and the Dogs" (though for some reason the book was translated into English as The Time of the Hero). But the film shows much less of the city and much more of the dogs than does Vargas Llosa's novel, whose first edition came complete with a map of Lima. Lombardi keeps us mostly within the claustrophobic confines of the military academy in which the "dogs," the army cadets, have forged a rough and tumble community whose hierarchies, values, and abuses both challenge and mirror those of the army, and by extension the nation, itself.Lombardi also narrows his focus among the group of cadets. The book is notable for employed a narrative style that switches constantly between narrators and perspectives, creating the overall effect of portraying the "dogs" as a kind of multiform, collective subjectivity. Moreover, Vargas Llosa's novel hides a huge twist in its tail, as on what is practically the book's final page we suddenly take stock of a dramatic breach between interior monologue and external appearance. Sadly but perhaps inevitably the film excises these properly literary effects, to concentrate on the figure of one Alberto Fernández, nicknamed "the poet," who functions mostly as an observer through whom we in turn apprehend other characters and the actions they undertake.

The cohort's top dogs are a group of four cadets known as "the circle," led by a striking young touch nicknamed the "Jaguar," who run a thriving black market trade in cigarettes, liquor, pornography, and stolen exam papers for the other inmates of this military boarding school. The film's plot kicks off as the theft of a Chemistry exam is discovered by the academy's authorities, and as a result the four cadets who were on guard at the time of the theft have all their weekend leave cancelled. One of the four is a boy who inhabits the very lowest rung of the savage hierarchy that the cadets have established, as is indicated by the nickname they've given him: Ricard Arana is better known as the "Slave." The Slave has managed to pass three years in the institution without making a single friend, except perhaps the Poet himself, to whom he pours out his troubles. The Slave is particularly agonized by the fact of his confinement, as it means he's unable to meet up with the neighborhood girl, Teresa, to whom he's shyly taken a fancy. Little does he know that in fact his only friend, the Poet, has started up a relationship with Teresa himself.

The Slave then commits the worst sin imaginable among the boys: he betrays the group by turning stool pigeon in order to have his exit privileges reinstated. As a result, the exam thief, Cava, a member of the circle, is humiliatingly thrown out of the academy and his compadres vow revenge.

During live ammunition exercises in the countryside, the Slave is shot and mortally wounded. The authorities, hushing up the scandal, declare that young Ricardo accidentally killed himself with his own rifle. But the Poet suspects a more likely narrative: that the Jaguar took rough justice into his own hands, gunning down the weakling who had dared to question his group's authority.

During live ammunition exercises in the countryside, the Slave is shot and mortally wounded. The authorities, hushing up the scandal, declare that young Ricardo accidentally killed himself with his own rifle. But the Poet suspects a more likely narrative: that the Jaguar took rough justice into his own hands, gunning down the weakling who had dared to question his group's authority.And so the Poet himself, agonized by his own betrayal of the dead boy, in turn decides to inform on the circle and incriminate the Jaguar. He convinces one Lieutenant Gamboa of the truth of his account: that the cadets are essentially beyond the control of the institution, and that their leaders feel they can even get away with murder. Gamboa, portrayed as a decent man who's prepared to risk his career in the name of what is right, forces the issue through to his superiors. But little justice is done: the cover-up continues, Gamboa is transferred out to a remote posting in the Andes, and the only (albeit perhaps the most devastating) punishment that the Jaguar receives is to be overthrown by those who were previously his loyal henchmen.

In the end, though the film presents itself as an incisive critique of the corruption and machismo that dominate both the cadet cohort and the army as a whole, it's unclear what if any values it upholds. It's difficult not to feel some sympathy for the Jaguar, who so stubbornly upholds his own code of honour that he refuses to clear at least some part of his disrepute by squealing in turn on the Poet's act of treason. Indeed, in some senses the Jaguar is the only figure who avoids the taint of treason: even Gamboa, given a final chance to prove the truth of what has taken places, rips up the evidence before heading out of the school gates and on to his lonely highland exile. The Jaguar believes in his strict moral doctrine because he has nothing else to believe in. But it is this rigidity that leads to the Slave's demise. It's the demand for absolute solidarity that drives a merciless scapegoating.

YouTube Link: Cava's expulsion.

No comments:

Post a Comment