But Salvador’s national food is the pupusa: a tortilla stuffed with cheese or beans. You can buy them hot off the grill at any market or street corner in provincial towns. A few days later, amid the bustle of a place called San Francisco Gotera in which the central plaza was over-run by market stalls, I sat down for some pupusas. Hot, greasy, overloaded with melted cheese, they were delicious. They came with assorted pickled vegetables that I scooped up with the tortilla and my fingers. I downed the sweet, tepid coffee that was also on offer. And asked to pay. I didn’t quite understand reply, but I knew it was three something. I proffered three dollars, only to receive a laugh and two dollars twenty-five in change. It turns out that the Salvadorans, who abandoned colones for their currency and now rely on US greenbacks and coins, talk in terms of “coras” or “quarters.” The meal had been three quarters. Seventy-five cents, and no thought of taking advantage of my confusion.

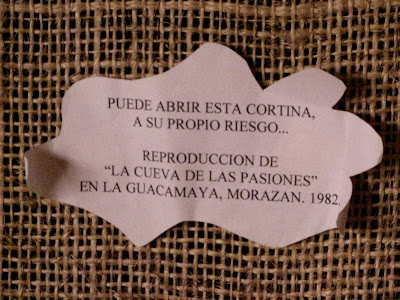

Back at the museum, I decided to try my luck and ring the bell to see if they’d let me in anyway. A woman answered and after a brief consultation welcomed me inside. But it wasn’t quite what I’d expected. I’d thought that this would be a monument to the war experience. I was somewhat chastened to discover instead an emphasis first on the indigenous culture of the West, and second an exhibition in preparation on the noted painter Salarrué. I was a fairly unabashed war tourist, but here I was brought up short. But in one room was a doorway covered by a rough mat curtain, on which was pinned a note saying “You can open this curtain at your own risk... Reconstruction of the ‘Cave of Passions,” in La Guacamaya, Morazán, 1982.”

I took the risk and moved the cloth aside, to find a darkened room with a couple of chairs and a bank of aged radio equipment. This was the small homage to Radio Venceremos, the guerrilla radio, in the museum run by its most famous representative, a man who still went by his nom de guerre of "Santiago.".

But it was as though hiding the “cave of passions” were both a rebuke to the over-nostalgic seeking to relive some kind of war experience, and also a reminder to others of passions that still lay just a twitch of a curtain away. It was a gesture of showing and not showing, insisting either way that there was more to the country than you might have thought.

No comments:

Post a Comment