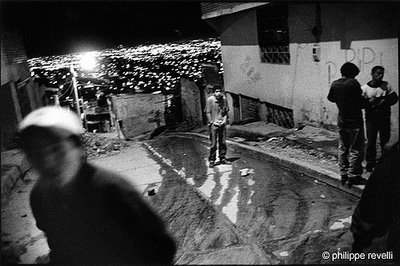

Alicia Velásquez Nimatuj offers a stirring defence of Guatemalan indigenous dress or traje. She opens with an anecdote of how she was refused admittance to a Guatemala City restaurant solely (she tells us) because she was wearing K'iche dress. She argues that wearing traje "is not just a matter of standing up for our cultural rights. Since 1997, in post-war Guatemala, it has become a political challenge: that of breaking the various ideological, legal, colonial, and contemporary racist structures that exist in all spheres of the Guatemalan State" ("Ways of Exclusion" 158).

Alicia Velásquez Nimatuj offers a stirring defence of Guatemalan indigenous dress or traje. She opens with an anecdote of how she was refused admittance to a Guatemala City restaurant solely (she tells us) because she was wearing K'iche dress. She argues that wearing traje "is not just a matter of standing up for our cultural rights. Since 1997, in post-war Guatemala, it has become a political challenge: that of breaking the various ideological, legal, colonial, and contemporary racist structures that exist in all spheres of the Guatemalan State" ("Ways of Exclusion" 158).But if the survival of traje is an instance of both "historical resistance" and "everyday resistance," indeed if in the history of Mayan resistance to colonialism "women's regional dress has played a leading role" (159), then what to say of the fact that increasingly, and especially in the cities, it is now replaced by "fashionable jeans and jacket" (161)? For Velásquez Nimatuj, the shift from regional to conventional Western dress shows "how racism is internalized for some Maya women [. . . they] have come to accept what the dominant ideology has repeated over and over again, that our regional dress stands for 'backwardness,' 'underdevelopment,' 'poor hygiene,' 'ignorance,' and 'living in the past'" (160).

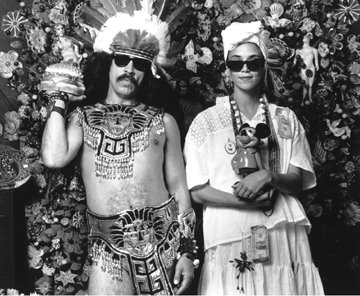

On the other hand, the role of "Maya intermediaries" in "the folkloric exploitation and abuse of Maya women and their traditional dress" is equally "reprehensible" (162). Velásquez Nimatuj notes that "sadly" even "a few Maya" are involved in organizing Cobán's annual folk festival that features a beauty pageant for indigenous girls in ceremonial costume (162).

In short, both wearing traje and not wearing it properly, treating it as semi-archaic folklore rather than as living resistance, are equally damned as something very close to ethnic betrayal.

Indigenous dress threatens both betrayal and counter-betrayal: in so far as it constitutes the performance of ethnic authenticity and resistance, it "betrays" the fact that its wearer will never be fully ladinized, that she is always treated as stubbornly subaltern to be banished to the margins of Guatemalan society; but by contrast, when the dress is put centre-state as the fetishized image of national identity, for instance in airport shops or tourist brochures and boutiques, another betrayal is afoot in this improper performance of authenticity.

In other words, though Velásquez Nimatuj wants to tell us that dress somehow expresses the intimate essence of ethnic identity, "the visible proof and cultural marker that locates us in the category of 'Indians'" (160-161), not only does she therefore collude with the restaurant doorman who likewise interprets clothing as ethnicity, but she is also forced rather futilely to police the evident fissures between the two. She insists that studies focussing only on the material aspects of indigenous weaving are insufficient, but this is surely because now traje has become for her a political style on which she, like any other self-appointed arbiter of fashion, has set herself up to judge.

By contrast, then, I find Carol Hendrickson's more nuanced analysis to be also more persuasive. For Hendrickson, wearing regional dress is best understood as strategy rather than essence, allowing "Guatemalans acting within a given social moment [to] contemplate and adjust their own appearance (if only momentarily and on an extremely small scale) and hence the social role assigned to them" ("Images of the Indian in Guatemala" 303). As a strategy, then, the consequences of traje are never fully predictable. It is an always uncertain risk, which may bring rewards as well as stigma, benefits as well as losses. "This is particularly true when the situation is anything more than routine and when it is not obvious which image of the Indian will come into play for any particular circumstance" (304).

Velásquez Nimatuj prescribes pre-destined resistance, whose limits she claims to legislate as native anthropologist/informant. But Hendrickson presents dress as a terrain of corporeal experimentation and investment, which may or may not lead to politically significant incorporeal transformations, in a contested field in which identity traits are at least partially dislocated and so still up for grabs.