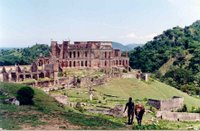

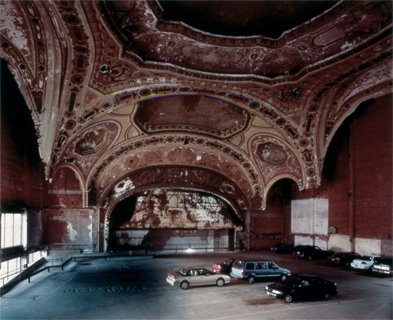

I have discussed ruins before, and one of my side projects is a book on what I call "American Ruins." The idea is to analyze a number of exemplary but rather different ruins from this hemisphere: Vilcashuamán, Peru; Sans Souci, Haiti (which is the image to the right); the Michigan Theater, Detroit (at the bottom of this post); Pino Suárez metro station, Mexico; and the Ochagavía hospital, Chile.

I have discussed ruins before, and one of my side projects is a book on what I call "American Ruins." The idea is to analyze a number of exemplary but rather different ruins from this hemisphere: Vilcashuamán, Peru; Sans Souci, Haiti (which is the image to the right); the Michigan Theater, Detroit (at the bottom of this post); Pino Suárez metro station, Mexico; and the Ochagavía hospital, Chile. Just now I'm finishing up a paper that focusses on the first of these, Vilcashuamán. Here are the first couple of paragraphs of that paper, outlining the conjunction between American-ness and ruination. (Post-9/11 there are others, of course.) Sadly, Scott won't like the last line. But there we go...

There is no such thing as an ancient ruin, for the ruin is always a modern concept. Ruination and modernity go hand in hand, as the modern displaces the ancient, marks it as irredeemably part of the past precisely by construing it as ruined. Ruins are the site of what has been put behind us. But at the same time they remain front and center: for modernity occasions a sometimes anxious reflection on the conditions and effects of “progress,” on this process of temporal displacement for which the ruin serves as a memento mori. Modernity creates the ruin as something both to be discarded and also to be read, obsessively. We moderns construct and interpret ruins as judgment on the past and warning for the future. “Men moralize among ruins,” observed Benjamin Disraeli, “or, in the throng and tumult of successful cities, recall past visions of urban desolation for prophetic warning. London is a modern Babylon; Paris has aped imperial Rome, and may share its catastrophe” (138). A sign of modernity’s success and vitality is that past civilizations are in ruins all around; but they remind us that there can be no guarantee that today’s proud edifices will not, in turn, fall to rack and ruin. Ruins demonstrate that whole cultures, just like the lives of mortals, are transient. Hence they are invented by cultures that feel their own transience. And no culture feels more transient than the American.

Though the Americas have long been envisaged as the “New World,” and despite Goethe’s assertion that “America, you have it better / Than our old continent; / You have no ruined castles / And no primordial stones” (qtd. Lowenthal 110), in fact the hemisphere has more than its share of ruins. This should be no surprise: modernity was after all abruptly conceived in the encounter between Old and New Worlds, and built upon the ruins of the civilizations first encountered by the Spanish conquistadors. The traces of imperial grandeur are now themselves ruined, and where there are no ruins easily to hand, they have often enough been built from scratch or substitutes have rapidly been found. From Hearst Castle or campus gothic to the dinosaur bones patronized by tycoons such as Andrew Carnegie, as the US became the dominant world power at the end of the nineteenth century and in the first decades of the twentieth, it increasingly sought out its own ruins. Frequently, those ruins were south of the border: this was also the heyday of a burgeoning archaeology, and the discovery of “lost” cities in rainforests and remote valleys the length and breadth of the continent. Today, ruins are big business (Tikal, Tenochtitlan), even as big business leaves its own ruins behind (from the Rust Belt to reclaimed factories).

No comments:

Post a Comment