Gioconda Belli's The Country Under My Skin documents both the euphoria and the disappointment of the Nicaraguan revolution. It's also a meditation on the relations between power, affect, and knowledge. And it's a seductive tale warning of the dangers of seduction.

Gioconda Belli's The Country Under My Skin documents both the euphoria and the disappointment of the Nicaraguan revolution. It's also a meditation on the relations between power, affect, and knowledge. And it's a seductive tale warning of the dangers of seduction.Belli is in Costa Rica in the days leading up to Somoza's downfall, frustrated about her distance from the real action. But thanks to her access to radio communications with rebel commanders on the front lines, she is able to follow the action if anything more closely than most of those on the ground: "It was mesmerizing to hear about the progress of the insurrection, to hear what was happening in real time" (234).

The final weeks and months of the Sandinista triumph went by astonishingly rapidly. Rather than leading, the Sandinistas were running to catch up with their impending triumph. Belli captures the "sensation of unreality" as victory finally, unexpectedly, raced up to meet them and the FSLN were thrust, blinking in the light, onto the world stage: "Sometimes it seemed as though they couldn't be talking about my tiny country, abandoned by everyone and beholden to a bloody dictator for half a century, but about a major power, able to make policy decisions that would alter Latin America's future" (236).

And then suddenly, almost anticlimactically, Somoza leaves office. And the Sandinistas, as much as anyone else, are left wondering what happens next: "Nobody spoke. Nobody moved. Everyone's eyes glittered with anticipation" (239).

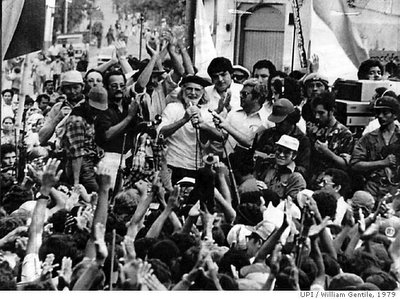

Then the celebration: "Overcome with joy, we fell into one another's arms. 'Somoza left!' we repeated to each other, as we kissed, danced and hugged." And Belli echoes Neruda's famous "Heights of Macchu Picchu" in her invocation of the dead reborn in triumph: "Multitudes of our beloved dead came to life among us with their empty eyes, their deaf ears, the dust of their bones that could never celebrate with us" (239). It's a mythic time of (re)creation: "The 18th, the 19th of July 1979. [. . .] Two days that felt as though a magical, age-old spell had been cast over us, taking us back to Genesis, to the very site of the creation of the world" (241).

Such is the world-making power of revolutionary violence.

But Belli, closely associated with the cúpula of the FSLN leadership, is soon entrusted with part of the transformation of that constituent power into constituted power: the construction of a nation, reconstruction of the state. Her task is to represent the revolution, to produce the "victory issue" of a new newspaper, to be called Patria Libre. This task can only be completed from the distance that representation requires, the newspaper then imported into the newly liberated country.

Flying into Managua on a plane loaded down with newsprint, Belli finds the airport almost deserted: the action is elsewhere. Only an old school friend has turned up to greet her, but Belli turns her away, judging her guardianship of the papers to be more important. Here, even at arrival, is the first disappointment, the first betrayal, of the revolution: over the "eerie desolation" of the airport terminal "Justine's face would be always superimposed. I managed to shake off my uneasiness. There would be time later on to explain things to Justine, to my parents, I said to myself. They would wait for me, they always did. But history wouldn't" (246).

Belli sets off, with her precious copies of Patria Libre, seeking to track down the history that the newspaper already claimed to represent. Her truck passes jubilant crowds: "their joy had the taste of sweet, red watermelon, its juice dripping down my chin" (247). But when at last they get to the city and reach the central plaza "there was no one left. That was when we realized that the crowds we'd seen on the road had been walking home after the celebration. All that was left in the great, deserted plaza were wrappers, trash" (248).

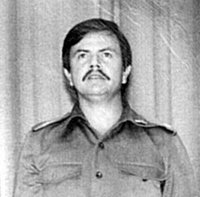

In place of this unpredictable, mobile multitude, the Sandinistas establish a militarized state as totem and fetish, positing its institutions and its leaders as the object of revolutionary desire--thus inverting the relationship constitutive of the triumph itself. Belli notes the demobilizing effect of this inversion, describing her lover Modesto and his "bodyguards, who only a month earlier had fearlessly confronted Somoza's tanks, [and now] were docile and obedient in their leader's presence" (266).

In place of this unpredictable, mobile multitude, the Sandinistas establish a militarized state as totem and fetish, positing its institutions and its leaders as the object of revolutionary desire--thus inverting the relationship constitutive of the triumph itself. Belli notes the demobilizing effect of this inversion, describing her lover Modesto and his "bodyguards, who only a month earlier had fearlessly confronted Somoza's tanks, [and now] were docile and obedient in their leader's presence" (266). She observes the ways in which "military protocol had its grandiose, seductive side. [. . .] Modesto--comandante, member of the Sandinista National Directorate, maximum authority in Nicaragua both during and after the Revolution--would move calmly amid the soldiers hurriedly standing at attention" (266).

It's not long before Belli also realizes that "the dazzling spell of power"--constituted power, we should clarify--also entails self-delusion among those who wield it: "these men had been seduced by the spell of their own self-image [. . .]. They felt eminently astute and capable, a cross between political bright boys and heroic, strapping knights-errant" (275).

The Sandinistas begin to believe their own myth of leadership, rather than learning from their experience of belatedness. The only indication of what has been lost in this transition is the lingering nostalgia that pervades Belli's memoir, a "nostalgia for what we had been" (291) before the rigidity that set in with the state's consolidation, and before the FSLN retrospectively branded everything in sight with their red and black logo.

No comments:

Post a Comment