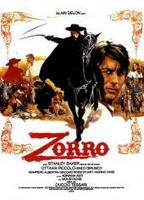

Another day, another Zorro movie. And Alain Delon's Zorro comes with a cheery theme song, courtesy of Oliver Onions. I defy you to listen to it (and you can find a clip here) and not feel, well, something. And the lyrics...

Another day, another Zorro movie. And Alain Delon's Zorro comes with a cheery theme song, courtesy of Oliver Onions. I defy you to listen to it (and you can find a clip here) and not feel, well, something. And the lyrics...Here's to you and meNow, c'mon, what more do you want?

Here's to being free

La la la laaa la la

Zorro's back.

This 1975 version takes the Zorro story from California and transports it to some generic tropical Latin American locale. The skies are blue, the nights are humid, the aristocrats and their servants are baroque and bewigged, the people are enslaved, and, yes, Zorro is back. Indeed, the sequence showing his arrival is splendid: in the middle of a scene taken directly from the 1920 Douglas Fairbanks movie, in which a priest is whipped for allegedly selling underweight goods, parallel edits show the dark figure of the masked avenger gradually coming into focus silhouetted against the azure sky. "Enough!" he declaims. "I want to show you what justice is."

Power is ever more centrally at issue in this version of the story. Power and its disguises. For here Zorro is the outcome of a double disguise: Alain Delon's character, Don Diego, whose real origin and role are murky, first stands in for the governor Miguel de la Serna, murdered at the outset by the dastardly Colonel Huerta, before he subsequently also transforms himself into the bandit with a conscience.

Don Diego therefore impersonates both legitimate power (as his Excellency the governor) and illegitimate counter-power (as the masked brigand). In both roles, however, he is restrained from violence by his promise to the dying de la Serna, in which he swore to uphold the good governor's ideals. Only in the climactic final scene, in which Huerta cold-bloodedly kills the (same) priest, Brother Francisco, to avert a social revolution, does Zorro feel that he is released from that promise. Huerta is duly despatched, albeit after a protracted fight sequence.

Then, in marked contrast with Tyrone Power's incarnation, Zorro rides off into the distance, leaving behind even his love interest, the fair (if somewhat ornery) Contessina Ortensia Pulido.

Then, in marked contrast with Tyrone Power's incarnation, Zorro rides off into the distance, leaving behind even his love interest, the fair (if somewhat ornery) Contessina Ortensia Pulido.This is, in short, a much less territorialized Zorro than either the 1920 or (particularly) the 1940 outings.

The fictional territory in which the action takes place is named either Nueva Aragon or Nuova Aragona: the movie is uncertain even as to its linguistic affiliations, and is dubbed into English from what could quite possibly have been a Babelic confusion of languages used on set. The colonial outpost depicted is an (almost) any-space-whatever of 70s exoticism: it might as well be Mozambique or Tangiers. (The very similar Burn! was in fact shifted during production from the Spanish Empire to the Portuguese.) What's important about the locale is that almost everything is out of place. This is a faux-European society imposed on the barren land of the Third World.

So no surprise that Zorro himself is very much a man of no fixed abode, a nomad who can only impersonate belonging. Here, almost everything is a matter of impersonation.

What's highlighted is the very ridiculousness of colonial society. In fact, this is a theme that underlies all Zorro films, however much at the same time they attempt to naturalize and legitimate the ideal of a benevolent imperialism.

What's highlighted is the very ridiculousness of colonial society. In fact, this is a theme that underlies all Zorro films, however much at the same time they attempt to naturalize and legitimate the ideal of a benevolent imperialism. The films derive their comedy from the antics of Don Diego as fop (here magnificently realized in a scene in which the governor rises from his throne to greet the visiting Pulidos only immediately to trip and fall headfirst on the ground). And Don Diego, in his uselessness, idleness, and futility, is always typical of the ruling colonial class. Which is why, after all, he has to become Zorro, i.e. to step outside that class, in order to reform it.

But whether incarnated in Zorro or Don Diego (here, impersonating governor Miguel de la Serna), what Delon's film more than any other underlines is the performativity of power.

[Meanwhile I note that Isabel Allende has written a Zorro novel. God help us all...]

(Crossposted from Latin America on Screen.)

No comments:

Post a Comment