The Commonwealth semi-periphery, for instance, is cast as a redoubt of mid-century English innocence. Writing in The Times, Arnie Wilson cites what he calls "that traditional Kiwi joke: 'We’re about to land in Auckland — please put your watches back 50 years.'" Victoria, British Columbia, has also been described in similar terms.

The Commonwealth semi-periphery, for instance, is cast as a redoubt of mid-century English innocence. Writing in The Times, Arnie Wilson cites what he calls "that traditional Kiwi joke: 'We’re about to land in Auckland — please put your watches back 50 years.'" Victoria, British Columbia, has also been described in similar terms.In the periphery itself, travelers are apt to find Dickensian exploitation, feudal simplicity, Stone Age barbarism, or even prehistoric lost worlds, depending upon inclination.

Alejo Carpentier's The Lost Steps (Los pasos perdidos) is a classic narrative of this spatialization of time: its narrator has to undertake a tortuous journey through a maze of Amazonian waterways in his quest to find the origin of music, the primitive foundation of melody and rhythm. At each turn he peels back decades, centuries of time passed and forgotten by "civilized" man.

But, as Mary Louise Pratt shows in her reading of Alexander Von Humboldt's travel writings, precisely the same gesture positing the Third World as some primal past also frames it as the site from which the future will be born. If Latin America was "a primal world of nature, an unclaimed and timeless space [. . .] whose only history was the one about to begin," then it could also be envisaged as "point of origin for a future that starts now, and will rework that 'savage terrain'" (Imperial Eyes 126, 127).

It is because America is our past that it can be, in Hegel's famous words, "the land of the future, where, in the ages that lie before us, the burden of the World's History shall reveal itself."

For Pratt, it is Humboldt who most persuasively and influentially articulates this sense of the Americas as a continent pregnant with possibilities for investment and growth:

On the eve of Spanish American independence and the eve of a capitalist 'scramble for America' not unlike the scramble for Africa still to come, Humboldt's Views and his viewing stake out a new beginning of history in South America. (127)Humboldt's portrayal of the American landscape in terms of its dynamism, worked over by the "occult forces" of geology and climate, resonates as much with "industrialism and the machine age" as it does with the "spiritualist esthetics of Romanticism" (124). The region's immense forests, mountains, and plains constitute a natural factory: a complex mechanism characterized above all by its productivity.

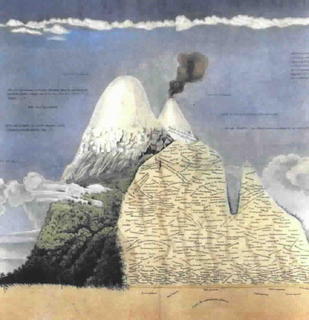

After all, doesn't Humboldt's sketch of Chimborazo resemble nothing so much as a nineteenth-century factory, complete with its innards dissected and delineated according to the natural division of labour, and its serrated roof topped by a chimney belching smoke into the blue sky?

Pratt quotes from the Preface to Humboldt's Personal Narrative, which predicts an age in which:

the inhabitant of the banks of the Oroonoko will behold with extasy, that populous cities enriched by commerce, and fertile fields cultivated by the hands of freemen, adorn those very spots, where, at the time of my travels, I found only impenetrable forests, and inundated lands. (qtd. 131)And as she notes, in this description of an "ecstatic future counterpart" who will see the results of "rapturous nature" harnessed to industrial commerce (131, 130), Humboldt's discourse is ultimately affective. "Humboldt sought," Pratt tells us, "to pry affect away from autobiography and narcissism and fuse it with science" (124).

In the jungles of Latin America--and this is how its landscape differs from the English Lakes or French Alps beloved of other Romantics--affect is envisaged as combining with science and harnessed to capital in the name of a utopian future of industrial enrichment.

No comments:

Post a Comment