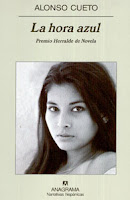

Whereas the Peruvian Alonso Cueto’s previous novel, with its title Grandes miradas (which could translate as something like “Broad Gazes”), suggested an interest in the visible, La hora azul (“The Blue Hour,” winner of the 2005 Herralde Prize) is all about the voice. Almost every character is identified by their distinctive voices; there is even one who has structured his entire wardrobe and habits around his voice, believing it to be “the best and most significant demonstration of his qualities as a Lima gentleman” (214).

Whereas the Peruvian Alonso Cueto’s previous novel, with its title Grandes miradas (which could translate as something like “Broad Gazes”), suggested an interest in the visible, La hora azul (“The Blue Hour,” winner of the 2005 Herralde Prize) is all about the voice. Almost every character is identified by their distinctive voices; there is even one who has structured his entire wardrobe and habits around his voice, believing it to be “the best and most significant demonstration of his qualities as a Lima gentleman” (214).It’s true that the story opens with a visual image: the photograph of an apparently enviably successful couple, published in the society pages of a glossy magazine. And moreover that the plot is put into motion by a written text, a letter that the novel’s protagonist, a Lima lawyer by the name of Adrián Ormache, finds among his recently dead mother’s effects. But the illusion created by the photograph is unreliable: the gloss of success conceals a sinister family secret. And the letter takes us back to the last words spoken by Adrián’s father, whose “hoarse voice,” a “voice of curt exclamations” (23), had spoken to him of a woman in the highland province of Ayacucho, a woman the son should try to find.

Adrián had taken little account of his father’s dying words, thinking them to be just another symptom of a final delirium. But then his brother, a brother who had “inherited the hoarse voice” of his father (22), tells the story of his father’s activities as military commander in Ayacucho during the war against Sendero Luminoso. Apparently, he used to round up women suspected of being Senderistas, bring them back to base and have sex with them, then pass them on to his junior officers who would also rape them, before delivering the coup de grace with a bullet in their brains. But there was one victim whom he kept to himself, locked up in his room. And this woman somehow escaped from her living hell of enforced servitude and torture. Was this living testament to his father’s brutality, the woman that Adrián was now to track down?

The plot, then, consists in the son’s attempt to locate the one who got away from his father. In part the quest is driven by the need to maintain her silence, to preserve family honour and professional decorum by ensuring that she doesn’t talk to the press. But Ormache’s investigation is also a journey into the bleak secrets of Peruvian society, the gap that separates rich and poor, coast and highlands, light-skinned and dark-skinned. To inform himself about the atrocities committed during the war, he reads a book entitled Las voces de los desaparecidos: “The Voices of the Disappeared.” There is an increasingly testimonial quality to the lawyer’s obsession and also therefore to the novelist’s design. La hora azul aims in part to give voice back to the subaltern voiceless.

But it’s not that Ayacuchan peasants have no voice; just that the Lima elite fail to recognize them. Indeed Miriam, Adrián’s father’s former prisoner, made good her escape from the military barracks by imitating the voice of one of her torturers. And on the other hand, the objects of the lawyer’s investigation manage to retain some sense of autonomy and control only by refusing to speak: for much of the novel they maintain a guarded silence, frustrating his attempts to reach out, to play the liberal who only wants to hear their stories. For when finally he does hear something of the violence and suffering that his father, amongst others, had inflicted on the highland population, the best that Adrián can come out with are the most banal of platitudes that leave even him feeling “insuperably ridiculous” (251).

Hence this mystery novel ends with silence on some of its main points. Miriam dies, we know not whether from an unexpected heart attack or by her own hand. Before her death, she had equivocated when asked whether or not her child was Ormache’s son, and so Adrián’s brother. Her uncle refuses to clarify things, saying only “with a velvety voice” that “she told me various things, but that is between her and me” (284, 282). And finally, the son himself, Miguel, is unnaturally silent. Adrián diagnoses this as a problem, and has him sent to a psychologist who promises to teach him to find his voice. But even so, and however much the protagonist declares that the poor, the people of Ayacucho, “are like us,” he remains unnerved and disconcerted by “their silence faced with the brutal repartition of death in which they have been born.” No wonder that he also concludes that “the line that separates us from them is marked by the blade of an enormous knife” (274).

It is the violence of hundreds of years of colonial and postcolonial oppression that ensures that the liberal project of “giving voice” is doomed to failure.

No comments:

Post a Comment