Me gustas cuando callas porque estás como ausente,

Me gustas cuando callas porque estás como ausente, y me oyes desde lejos, y mi voz no te toca.

Parece que los ojos se te hubieran volado

y parece que un beso te cerrara la boca.

Como todas las cosas están llenas de mi alma

emerges de las cosas, llena del alma mía.

Mariposa de sueño, te pareces a mi alma,

y te pareces a la palabra melancolía.

Me gustas cuando callas y estás como distante.

Y estás como quejándote, mariposa en arrullo.

Y me oyes desde lejos, y mi voz no te alcanza:

déjame que me calle con el silencio tuyo.

Déjame que te hable también con tu silencio

claro como una lámpara, simple como un anillo.

Eres como la noche, callada y constelada.

Tu silencio es de estrella, tan lejano y sencillo.

Me gustas cuando callas porque estás como ausente.

Distante y dolorosa como si hubieras muerto.

Una palabra entonces, una sonrisa bastan.

Y estoy alegre, alegre de que no sea cierto.

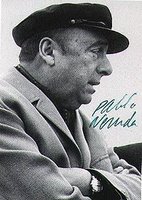

[Hear Neruda himself recite it, albeit rather dolefully, here (mp3).]

It's a tough poem to translate (though there are a couple of egregiously bad attempts out there, notably this one, which gets the last line utterly wrong).

Above all, no doubt, there's the question of how to translate "me gustas cuando callas." Among other efforts, I've seen "I like you calm," "I like it when you're quiet," and "I like for you to be still." And callarse does indeed have a range of meanings.

The Collins Spanish Dictionary provides the following: "to keep quiet, be silent, remain silent; (of noise) to stop; to stop talking (or playing etc); to become quiet; (of sea, wind) to become still, be hushed."

The Real Academia Española gives us:

callar. (Del lat. chalāre, bajar, y este del gr. χαλᾶν).

- tr. Omitir, no decir algo. U. t. c. prnl.

- intr. Dicho de una persona: No hablar, guardar silencio. Calla como un muerto. U. t. c. prnl.

- intr. Cesar de hablar. Cuando esto hubo dicho, calló. U. t. c. prnl.

- intr. Cesar de llorar, de gritar, de cantar, de tocar un instrumento musical, de meter bulla o ruido. U. t. c. prnl.

- intr. Abstenerse de manifestar lo que se siente o se sabe. U. t. c. prnl.

- intr. Dicho de ciertos animales: Cesar en sus voces; p. ej., dejar de cantar un pájaro, de ladrar un perro, de croar una rana, etc. U. t. c. prnl.

- intr. Dicho del mar, del viento, de un volcán, etc.: Dejar de hacer ruido. U. t. c. prnl. U. m. en leng. poét.

- intr. Dicho de un instrumento musical: Cesar de sonar. U. t. c. prnl.

It's clear from both that the word's primary meaning concerns voice or sound, and so only by extension the other senses implied by calmness or stillness. Moreover (as Ashea notes), the range of signification also encompasses, without being limited to, the Spanish equivalent of "shutting up": "¡Cállate!"

At first sight this is a disconcerting image: the poet silencing the woman's voice, or even suggesting that she shut up. Such silencing is a familiarly gendered move, of course, but we'd rarely expect such explicitness, in a love poem at least.

And the image remains disconcerting at second sight, too, because it is the beloved's imagined absence that's celebrated; this appears to be an encomium to distance: "I like you when you're quiet because it's as though you were absent."

Worse still, at third sight, the poet seems also to be delighting in positing the woman's death: "Distant and doleful as though you had died."

Can then it be redeemed--if indeed we should want to "redeem" it--by the final line's ironic twist, "And I'm happy, happy that in fact it's not true"? Perhaps indeed the mistranslation "And I am happy, happy of what, isn't certain" is symptomatic: the poem surely leaves the reader with a shiver of uncertainty. Can Neruda really mean what he's saying?

Yet this is hardly the only poem in the collection that praises the beloved's silence: "Ah silenciosa!" ["Ah, silent woman!"] is Poem 8's refrain. Or compare Poem 14: "Ah déjame recordarte cómo eras entonces, cuando aún no existías" [Ah let me remember you as you were then, when you still did not exist"].

The woman (or women) addressed throughout the twenty poems is always a shadowy figure, however often she is compared to the most concrete and tactile of substances: the earth, for instance, in Poem 1. She hovers perpetually between presence and absence and that, it seems, is how Neruda likes her.

Because in the end what's affirmed her is not the beloved herself, let alone "the real subjectivity of another person" as Joseph Kugelmass argues about a poem (14) that states, of all things, "Since I've loved you, you've seemed like nobody" ["A nadie te pareces desde que yo te amo"].

What's affirmed is the poet's voice. He has "forged" his beloved "like a weapon" ["te forjé como una arma"] (Poem 1), and throughout the collection runs the double sense of this forgery: as both something unreal, insubstantial, untrue; and also a creation that pays homage more to the creator than to to the created. No wonder the final poem resounds with the self-affirmation "I can write" ["Puedo escribir"] (Poem 20).

I can write... I can write... I can write... And Neruda can surely write. There's no question that these are marvellous, beautiful poems, deservedly famous. But we shouldn't perhaps lose sight of the disconcert--and indeed discordance--the shiver of uncertainty induced by the spectral presence of the woman who is invoked only to be despatched, conjured up to be absent even in her presence, excessively haunting but also enabling the master poet find his voice through her silence.

[Meanwhile, Marta Brunet provides a rather different take on subaltern silence--and treachery.]

No comments:

Post a Comment