On the face of it,

The Bridges of Madison County is a study in psychology: an Iowa housewife, Francesca, dies; among her effects her children discover the key to a closely-held secret, a brief but passionate love affair several decades previously.

Her secret is presented as the key to understanding this woman. Her diaries open up to her children another side to their mother, revealing her to be more than the mere inhabitant of a social role. Yet, within the logic of the secret itself (told in flashback) there is the question as to why she didn't take the chance to escape, to wander the world with the exotic National Geographic photographer who has entered her life and showed how everything might have been otherwise.

So, first: why? And then: why not?

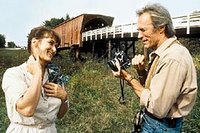

The notion that the film is psychological is emphasized by its format: almost a chamber piece with the bulk of the screen time taken up by the two characters of Francesca (brilliantly portrayed by Meryl Streep) and the photographer, Robert (Clint Eastwood). We are brought to these two subjectivities, one perhaps still only just burgeoning, at a moment of intensity.

But precisely this extreme focus, on these two people over just four days, already starts to give the lie to any psychological realism. We never get any sense, for instance, as to why the episode should have held such importance for Robert, whose character remains a cipher: he stands, rather abstractly, for exoticism and transience; otherwise, there is almost nothing to him. Nor, in the end, do we really see any deeper into Francesca's motivations: yes, we can understand that she might feel isolated and adrift in rural Iowa, but why really is she there in the first place? What holds her to her husband?

Streep give Francesca an interesting gesture, repeated so often it becomes a tic, a habit: she is endlessly putting her hand to her face, usually to half turn away. It is as though hiding behind her raised hand are inner depths that constantly elude us--and also Francesca herself, so deeply has she repressed her passions. But why insist on some depth beneath the gesture? Why not see the gesture itself as part of an affective mechanism, fully imbued with Francesca's desire.

The gesture of hand to face is complicated by a further gesture that Francesca (almost) makes near the film's end: rather than hand to face, now hand to (car door handle) as, in a crucial moment, she faces the choice of leaving her husband, his car, his life, and joining Robert who is in the truck up front, stopped at traffic lights in the rain. Hand to handle. Hand to handle. It starts to turn. But then the lights change and, after a pause, Robert heads off; Francesca stays, now putting hand to face again.

Hand - face - hand - handle: this minimal mechanism constitutes the film.

We might add, though, various lines of movement and change, along and beside which the mechanism operates: above all, the road leading to Francesca's isolated farmhouse, a road full of ups and downs, twists and turns, such that (as Robert finds when he first turns up on it), it's easy to get lost on it. The road brings Robert to her; it also takes her husband and children away, though then brings them back, while Francesca gazes again up the track hoping that Robert will reappear.

The road also leads (eventually) to a bridge, or rather a series of bridges, the eponymous covered bridges of Madison Country. Points of transition where the mechanism of transition (the crossing itself) is hidden: a black box in which what's to be found at the other side, or even whether one emerges out the other side at all, remains something of a surprise; these are sites of situations, of (possible) events. Will she cross? Won't she cross?

And yet the bridges hide nothing: there's no secret heart, (again) no psychological depth. Just a minimal series of gestures, a diagram with serried bifurcations, which may or may not prompt one body to take flight with another.

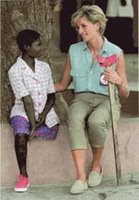

I had the good fortune this week to read a wonderful book proposal about development work, and more specifically the "desire for development," particularly among white women in the North.

I had the good fortune this week to read a wonderful book proposal about development work, and more specifically the "desire for development," particularly among white women in the North.