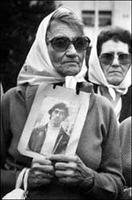

Discussing the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo, the Argentine women who stood up to their country's military regime of the 1970s and 1980s, demanding evidence about the whereabouts of their disappeared children, Diana Taylor suggests that "the Madres embodied 'pity' while the military males staged 'terror.'" Taylor continues:

Discussing the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo, the Argentine women who stood up to their country's military regime of the 1970s and 1980s, demanding evidence about the whereabouts of their disappeared children, Diana Taylor suggests that "the Madres embodied 'pity' while the military males staged 'terror.'" Taylor continues:But pity and terror are inextricably linked. As the Greek theatre scholar Gilbert Murray notes in his foreword to The Trojan Women, "pity is a rebel passion. Its hand is against the strong, against the organized force of society, against conventional sanctions and accepted Gods . . . it is apt to have those qualities of unreason, of contempt for the counting of costs and the balancing of sacrifices, of recklessness, and even, in the last resort, of ruthlessness . . . It brings not peace, but a sword" (7). The military, quick to pick up the threatening quality of the Madres' pitiful display of their wounds-as-weapons, branded the rebellious women emotional terrorists. (Disappearing Acts 200; emphasis in original)Pity and terror are linked, above all, because both are affects; both pity and terror sidestep "the counting of costs and the balancing of sacrifices"; both are excessive, unreasonable, qualitative and intensive rather than quantitative or extensive.

But what would make the one a "rebel passion" and the other an instrument of state power?

Surely the key here is in the distinction between embodiment and staging that Taylor invokes by stating that "the Madres embodied 'pity' while the military males staged 'terror'" (my emphasis). Embodiment and staging are two modes or aspects of performance (and Taylor's book is ultimately about the politics of performance in Latin American contexts), but they are quite different ways of thinking the performative.

"Staging" refers first and foremost to the instrumentality of performance, the distance between actor and act, between agent and identity. Both the military and the Madres performed in this sense. Above all, the Madres performed motherhood. In part this was to justify their activism as springing not from some political agenda, but from maternal instinct. But as a result, Taylor notes that they also played into a "bad script," an "Oedipal framing of events" that suggested that "equality and power [. . .] could only be regained by means of the restitution of the missing member," the absent son, "the lost phallus" (203).

Staging is the performative politics of identity: the Madres' presentation of themselves as pitiful (in both senses of the term) complemented rather than challenging the military males' narrative that only they could save the nation, could take the paternal role of reinstalling order.

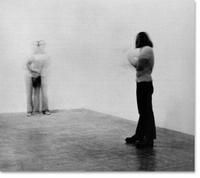

Embodiment, by contrast, refers to the fact that performance is also an affective and bodily investment. An actor puts his or her body on the line: when a character takes a tumble, so does the actor who plays him or her. Performance artists have experimented with this non-representational danger incarnated in the performative, not least Chris Burden in works such as "Shoot" and "Deadman".

Embodiment, by contrast, refers to the fact that performance is also an affective and bodily investment. An actor puts his or her body on the line: when a character takes a tumble, so does the actor who plays him or her. Performance artists have experimented with this non-representational danger incarnated in the performative, not least Chris Burden in works such as "Shoot" and "Deadman". The Madres knew only too well the risks that they were taking: as Taylor reports, in 1977 the military "infiltrated the Madres' organization and kidnapped and disappeared twelve women, including the leader of the Madres, Azucena de Vicenti" (187).

Embodiment, then, is performance without reserve: this is the reckless pity (the Derridean hospitality?) that know no bounds, that refuses the cost-benefit analysis that strategizing and instrumentality require.

There is a connection here to the distinction between constituent and constituted power, between the Spinozan power that knows no distance between possibility and reality (in fact, the virtual and the actual), and the sovereign Realpolitik that bides its time and chooses its moment, its victims.

But I'm reluctant simply to valorize reckless affect over either the strategy of war or even the "strategic essentialism" associated with Spivak's reading of the subaltern. There was, after all, something suicidal, hasty, and pitiful (something that went beyond a strategic miscalculation) about the Argentine junta's decision to invade the Malvinas/Falklands. Recklessness and investment without reserve is not the sole prerogative of the powerless. It can also be the state's most deadly transmutation.

No comments:

Post a Comment