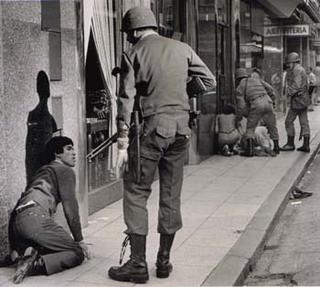

The Argentine death squads operated often with only the minimum of clandestinity: people were frequently disappeared in broad daylight, in the center of Buenos Aires. Little was hidden; the repression was out in the open. But people looked away. There's an amazing photograph in Diana Taylor's Disappearing Acts, for instance, of the moment of an abduction right in front of a downtown café's plate glass window. You can see a woman inside the café turning her head. Taylor terms this (self-)cauterizing of vision "percepticide."

Percepticide was justified by the notion that "there must be a reason." The abductee must have done something wrong to have been taken away by the state. "Por algo será." As Carlos Mangone notes, "por algo será" was "a phrase that marked civil indifference (and objective complicity) in the face of repression"; it indicated "a social psychology that calmed individual consciences and displaced the specter of thousands of human beings who had once had their own social, political, and cultural trajectories." The extinction of these thousands of individual histories was explained by the singularity of an unimpeached state logic.

We can uncover a similar logic at work as details are revealed of the circumstances that led to the London police killing Jean de Menezes at Stockwell tube a couple of weeks ago. (See the ITV news report and coverage at Lenin's Tomb.)

We were originally told by eyewitnesses that de Menezes was of Asian appearance, wearing a bulky jacket, wires protruding, and that he jumped the station barriers, running down to the train. Now it turns out that all these details were wrong. He was Brazilian (and relatively light-skinned, for what that's worth), in a light denim jacket, no wires, who went through the barriers in the normal way, stopping to pick up a newspaper, ran to catch the train, and sat down in his seat.

The original accounts, then, are symptomatic of a social fantasy secured by the state. They are elaborated from the original acquiescence that assumes that "por algo será," "there must be a reason," and proceeds to conjure one (or here, several) out of the confusing series of sensations produced in the event itself.

But the police too are victims of this same social fantasy. Hence the detail of the de Menezes's alleged "Mongolian eyes" that lenin mentions at Lenin's Tomb. In other words, rather than conspiracy or cover-up (though it is clear that, in denying that there were CCTV images of the incident, the police have subsequently if rather half-heartedly attempted some kind of cover-up), we see how police and public alike are subject to the state's capacity to organize our perceptions, to secure our complicity with its violence at some level far beneath consciousness.

[edited, having found the photograph in question on the web, and so also to correct the fact I had (mis)remembered the person in the cafe being male]

No comments:

Post a Comment